When cells of the lung start growing rapidly in an uncontrolled way, the condition is called lung cancer. This disease can affect any part of the lung, and it's the leading cause of cancer deaths in both women and men in the United States, Canada, and China.

There are two main types of lung cancer. Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC), sometimes called small-cell carcinoma, causes about 10%-15% of all lung cancer. Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) causes the rest.

2 Types of SCLC

There are two main types:

- Small-cell carcinoma (oat cell cancer)

- Combined small-cell carcinoma

Both include many types of cells that grow and spread in different ways. They’re named according to what the cells look like under a microscope.

Small-cell lung cancer differs from non-small-cell lung cancer in some key ways. Small-cell lung cancer:

- Grows rapidly.

- Spreads quickly.

- Responds well to chemotherapy (using medications to kill cancer cells) and radiation therapy (using high-dose X-rays or other high-energy rays to kill cancer cells).

- Is often linked to distinct paraneoplastic syndromes, a collection of symptoms that result from substances that the tumor makes.

Small-Cell Lung Cancer Causes

The main cause of both small-cell lung cancer and non-small-cell lung cancer is tobacco smoking. But small-cell lung cancer is more strongly linked to smoking than non-small-cell.

Even secondhand tobacco smoke can make you more likely to get lung cancer. If you live with a smoker, your chances of getting NSCLC go up by about 30%, and your odds of getting SCLC rise by about 60%. That’s compared to people who aren’t exposed to secondhand smoke.

All types of lung cancer develop more often in people who mine uranium, but small-cell lung cancer is most common. The prevalence goes up even more in uranium miners who smoke.

Exposure to radon -- an inert gas that develops from the decay of uranium -- has been reported to cause small-cell lung cancer.

Exposure to asbestos greatly increases the risk of lung cancer. A combination of asbestos exposure and cigarette smoking increases the risk even further.

Small-Cell Lung Cancer Symptoms

People with small-cell lung cancer typically have symptoms for about 2 to 3 months before they visit their doctor.

The symptoms can result from local growth of the tumor (meaning growth in the lung where it started), spread to nearby areas, distant spread, paraneoplastic syndromes, or a combination of some of these.

Some symptoms due to local growth of the tumor are:

- Cough

- Coughing up blood

- Shortness of breath

- Chest pain that gets worse with deep breathing

Some symptoms due to spread of the cancer to nearby areas are:

- Hoarse voice from compression of the nerve that supplies the vocal cords

- Shortness of breath from compression of the nerve that supplies the muscles of the diaphragm or from the lungs filling with fluid. It’s also possible to have stridor, a sound produced by turbulent flow of air through a narrowed part of the respiratory tract. This results from compression of the trachea (windpipe) or larger bronchi (airways of the lung).

- Trouble swallowing from compression of the esophagus (food pipe)

- Swelling of the face and hands from compression of the superior vena cava. That’s the vein that returns deoxygenated blood from the upper body.

Symptoms due to distant cancer spread depend on where it spread. Here are some examples:

- Spread to the brain can cause headache, blurry vision, nausea, vomiting, weakness of any limb, mental changes, and seizures.

- Spread to the vertebral column can cause back pain.

- Spread to the spinal cord can cause paralysis and loss of bowel or bladder function.

- Spread to the bone can cause bone pain.

- Spread to the liver can cause pain in the right upper part of the abdomen.

Some symptoms due to paraneoplastic syndromes are:

When to Seek Medical Care

Call your doctor right away if you have any of these symptoms:

- Shortness of breath

- Coughing up blood

- Unexplained weight loss

- Voice change

- New cough or change in the consistency of a cough

- Unexplained persistent fatigue

- Unexplained deep aches or pains

Call 911 if you have any of these symptoms:

Exams and Tests for Lung Cancer

If your doctor thinks you might have lung cancer, they’ll give you a physical exam. They’ll also ask about your health history, your work, any surgeries you’ve had, and whether you smoke or have in the past.

They may also give you exams and tests like these:

- Chest X-ray

- CT scan of the chest: An X-ray machine linked to a computer takes a series of detailed pictures of the inside of the chest from different angles. Other names of this procedure are computed tomography, computerized tomography, or computerized axial tomography.

- Thoracentesis: The lungs are enclosed in a sac. Lung cancer can cause fluid to collect in this sac. This is called pleural effusion. In people who have cancer, this fluid may contain cancer cells. The fluid is removed by a needle and examined for the presence of cancer cells.

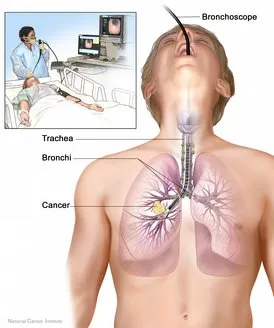

- Bronchoscopy: This is a procedure used to look inside the trachea (windpipe) and large airways in the lung for abnormal areas. A bronchoscope (a thin, flexible, lighted tube with a tiny camera on the end) is inserted through the mouth or nose and down the windpipe. From there, it can be inserted into the airways (bronchi) of the lungs. During bronchoscopy, the doctor looks for tumors and takes a biopsy (a sample of cells that is removed for examination under a microscope) from the airways.

- Lung biopsy: If a tumor is on the periphery of the lung, it may not be seen with bronchoscopy. Instead, a biopsy sample has to be taken with the help of a needle inserted through the chest wall and into the tumor. This procedure is called a transthoracic needle biopsy.

- Mediastinoscopy: This procedure is performed to determine the extent the tumor has spread into the mediastinum (the area of the chest between the lungs). Mediastinoscopy is a procedure in which a tube is inserted behind the breastbone through a small cut at the lowest part of the neck. Samples of lymph nodes (small, bean-shaped structures found throughout the body) are taken from this area to look for cancer cells.

If your doctor diagnoses you with lung cancer, they’ll recommend you get other exams and tests to find out whether the cancer has spread (metastasized) to other organs. These tests help determine the stage of the cancer.

Staging is important because lung cancer treatment is based on the stage of the cancer. Tests used to detect the spread of cancer may include:

- Blood tests: Complete blood count -- CBC -- provides information about the type and count of different types of blood cells, serum electrolytes, kidney function, and liver function. In some cases, these tests may spot where the cancer has spread. These tests are also important to check on how well your organs are working before you start treatment.

- CT scan of the chest and abdomen: An X-ray machine linked to a computer takes a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body from different angles. The doctor may inject a dye into a vein. They may have you take a substance called a contrast agent by mouth. It helps your organs or tissues show up more clearly on the scan.

- MRI: This makes high-quality images of the inside of the body. A series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body are taken from different angles. The difference between an MRI and CT scan is that MRI uses magnetic waves, whereas CT scan uses X-rays for the procedure.

- Radionuclide bone scan: With the help of this procedure, the doctor determines whether the lung cancer has spread to the bones. The doctor injects a small amount of radioactive material into the vein; this material travels through the bloodstream. If the cancer has spread to the bones, the radioactive material collects in the bones and is detected by a scanner.

- PET scan: A small amount of radioactive material is injected into the bloodstream and is taken up by cells that are very active, like cancer cells. This helps show where the cancer has spread.

- Video-assisted thoracoscopy (VATS): A doctor will insert a lighted tube with a video camera through small openings in the chest. It’s a way to look at the lungs and other tissue. A biopsy may also be done.

- Endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS): A doctor inserts a flexible tube with a video camera and an ultrasound attached, through your mouth and into your windpipe and lungs. They can look at the lungs and lymph nodes nearby and can take a biopsy of the tissue.

Staging

Staging of the cancer provides important information about the outlook of your condition and helps your doctor plan the best treatment. Small-cell lung cancer has two stages: limited and extensive. That makes it different from other cancers, which go from stage I to stage IV.

Limited stage SCLC. In this stage, the tumor is confined to one side of the chest, the tissues between the lungs, and nearby lymph nodes only.

About 1 in 3 people with SCLC have limited stage cancer when they first get diagnosed.

If that’s you, your doctor might recommend aggressive treatments -- meaning more intense than usual – to try to cure your cancer. For example, they might give you chemotherapy combined with radiation.

Extensive stage SCLC. In this stage, cancer has spread from the lung to other parts of the body. About 2 in 3 people with SCLC have extensive disease when they first get diagnosed.

Treatment can’t cure the disease, but it could ease your symptoms and help you live longer.

Small-Cell Lung Cancer Treatment

Some of the most commonly used combinations of medications used for SCLC are carboplatin (Paraplatin), cisplatin (Platinol- AQ), cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan), docetaxel (Taxotere), doxorubicin (Adriamycin, Rubex), etoposide (Vepesid), irinotecan (Camptosar), lurbinectedin (Zepzelca), paclitaxel (Onxol, Taxol), topotecan ( Hycamtin), and vincristine (Oncovin).

Treatment of limited-stage SCLC

Standard treatment of small-cell lung cancer involves combination chemotherapy with a regimen that includes cisplatin. Treatment cycles are typically repeated every 3 weeks. People receive treatment for four to six cycles.

Radiation therapy to the chest may be started as early as possible, or it may be given later in the course of treatment. This depends on things like the stage of your cancer and your overall health.

Radiation and chemotherapy: Some people get radiation followed by chemotherapy. But studies show that the earlier the radiation is started along with chemotherapy (as early as the first cycle of chemotherapy), the better the outcome.

If you have limited disease and you’ve had a very good response to chemotherapy, your doctor may recommend radiation therapy to your brain to lower the chances of small-cell lung cancer spreading there.

This is called prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI). It is usually given after you’ve completed the full chemotherapy and radiation therapy to the chest. The radiation doses are low, and the treatment duration is short, so the side effects of this therapy are minimal.

Treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer

People with extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer are treated with combination chemotherapy. The combination of etoposide plus either cisplatin or carboplatin is the most widely used regimen.

Radiation therapy may be used for relief of the following symptoms:

- Bone pain

- Compression of the esophagus, windpipe, spinal cord, or superior vena cava caused by tumors

- Obstructive pneumonia caused by the tumor

For people with newly diagnosed extensive small-cell lung cancer, doctors recommend the adding either atezolizumab or durvalumab to platinum (cisplatin or carboplatin) immunotherapy.

Treatment of relapse of small-cell lung cancer

A relapse is when your cancer or the signs of it come back after improving for a while.

If the disease doesn’t respond to treatment or gets worse after your initial treatment (called "refractory disease"), your doctor has other ways to ease your symptoms and help you live somewhat longer. They may recommend immunotherapy. If you’re not considered a candidate for immunotherapy, doctors typically use chemotherapy with topotecan (Hycamtin).

People whose cancer doesn’t get worse for more than 3 months may be given more chemotherapy, including another treatment with their original chemotherapy regimen.

People with relapsed or refractory small-cell lung cancer may enroll in a clinical trial. For information about ongoing clinical trials, visit the National Cancer Institute's Clinical Trials.

Your doctor can give you medicines to prevent and treat side effects of radiation, chemotherapy, or symptoms of the cancer itself, such as nausea or vomiting. Pain medications are also important to relieve any pain due to cancer or its treatment.

Surgery

Surgery plays little, if any, role in the treatment of small-cell lung cancer because almost all cancers have spread by the time they are discovered.

The exceptions are the relatively small number of people (less than 15%) who get diagnosed at a very early stage of the disease, when the cancer is confined to the lung without any spread to the lymph nodes. But surgery alone is not considered a possible cure, so they also get chemotherapy. Sometimes they also need radiation therapy if the cancer has spread to the nearby lymph nodes.

Other Therapy

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is the use of high-dose X-rays or other high-energy rays to kill cancer cells. Radiation can be given from outside the body using a machine (external radiation therapy), or it can be given with the help of radiation-producing materials that are implanted inside the body (brachytherapy).

Radiation therapy can be curative (kills all cancer cells), prophylactic (meaning it reduces the risk of cancer spreading to the area to which it is given), or palliative (helps ease pain and other symptoms).

Next Steps

Follow-up

- If you’re getting chemotherapy, your doctor will track your health closely for any side effects and to see if the treatment is working.

- You’ll need blood tests, including a CBC (complete blood count), before each cycle of chemotherapy. This ensures that your bone marrow has recovered before you get the next dose of chemo.

- Your doctor will check your kidneys, especially if you’re taking cisplatin since this drug can damage the kidneys. Also, carboplatin's dosage is based upon how well your kidneys are working.

- You’ll get a CT scan so your doctor can see how well you’re responding to the treatment.

- You’ll also need other tests to check on your liver function and electrolytes -- especially sodium and magnesium levels -- due to the effects of the cancer and its treatment.

Palliative and terminal care

Because small-cell lung cancer is diagnosed in most people when it is not curable, palliative care becomes important. The goal of palliative and terminal care is to manage pain and discomfort and enhance the quality of life.

Palliative care not only focuses on comfort but also addresses the concerns of the patient’s family and loved ones. Caregivers may include family and friends in addition to doctors, nurses, and other health care professionals.

Palliative and terminal care is often given in a hospital, hospice, or nursing home; however, it can also be provided at home.

Lung Cancer Prevention

Unlike many other cancers, lung cancer is linked to known risk factors for the disease. The main cause of lung cancer is tobacco smoking. So the most important way to help prevent lung cancer is to quit smoking.

Products that are available to help quit smoking include nicotine gum, medicated nicotine sprays or inhalers, nicotine patches, and oral drugs. Group therapy and behavioral training can also help you kick the habit.

For information about how to quit smoking, visit Smokefree.gov.

Other risk factors for lung cancer include asbestos, radon, and uranium exposure. Take precautions to avoid being exposed to these harmful substances.

Small-Cell Lung Cancer Prognosis

The success of treatment depends on the stage of small-cell lung cancer.

Unfortunately, in most people with small-cell lung cancer, the disease has already spread to other organs of the body by the time it is diagnosed. That shortens life expectancy.

The 5-year survival rate is between about 2% and 31%. That’s the percentage of people who are alive 5 years after they were diagnosed with or started treatment for a disease.

There’s no cure for advanced stage small-cell lung cancer, but doctors have lots of ways to improve your quality of life and ease any symptoms of the cancer or its treatment.

Support Groups and Counseling

Support groups and counseling can help you feel less alone and can improve your ability to deal with the uncertainties and challenges that cancer brings.

Cancer support groups provide a forum where patients with cancer, survivors of cancer, or both, can discuss the challenges that accompany the illness, as well as guide you in dealing with your concerns.

Support groups provide an opportunity to exchange information about the disease, give and take advice about managing side effects, and share feelings with others who are in a similar situation.

Support groups also help your family and friends deal with the stress of cancer.

Many organizations offer support groups for people with cancer and their loved ones. You can get information about such groups from your doctor, nurse, or hospital social worker.

The following organizations can help you with support and counseling:

- The Foundation for Lung Cancer operates a national "phone buddies" program, in addition to other services.

(800) 298-2436

[email protected] - The National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship is a survivor-led advocacy organization working exclusively on behalf of people with all types of cancer and their families.

- American Cancer Society

For More Information

American Cancer Society

(800) ACS-2345

American Lung Association

(800) LUNG-USA

(800) 586-4872

National Cancer Institute

(800) 4-CANCER

(800) 422-6237

American Society of Clinical Oncology

(888) 282-2552