Nov. 20, 2000 -- "Can anyone tell me what's involved in male reproduction?" a medical student in a white lab coat asks the young men scattered around a waiting room. "Don't be shy."

"The penis," a tough-looking teenager in a black leather jacket says softly, breaking the silence.

"This is the urethra," medical student Jason Klein continues, pointing to an illustration projected onto the wall. "Does anyone know what it does? Anyone? It's a tube that comes out of the penis, and urine and ejaculate come out of there."

He shows a photo of a pair of testicles. "Does anyone know what's wrong with this picture?" he asks, scanning the room as more people enter. Some of the guys are reading magazines. Others are whispering among themselves, and still others are staring into space zombie-like. "It's common for one testicle to lie lower than the other," Klein picks up. "It's completely normal and nothing to get worried about." Dressed in low-slung jeans and puffy jackets, the young men make a point of appearing not to listen, but their body language says otherwise.

Klein shows a photo of a penis covered with syphilis lesions and 19-year-old Rodrigue winces. When Klein holds up a long swab that doctors insert in a guy's urethra to get a tissue sample for an STD test, Rodrigue scrunches his face in horror and collapses onto his girlfriend's shoulder. Then Klein delivers the good news: "We don't have to use swabs anymore. Now you can just pee in a cup."

Welcome to the Young Men's Clinic of the Columbia University School of Public Health in New York, one of the few health clinics for men in the country. Klein, a fresh-faced, first-year medical student at Columbia, spends four hours a week at the clinic, which provides physicals, STD tests, and medical treatment to men aged 14 to 34 in Washington Heights, a community of Hispanics and African Americans. Many of these young men are on public assistance. More than 90 percent are sexually active, and a third have helped create a pregnancy. More than a quarter of guys who come here for a routine physical end up being treated for an STD.

"Neighborhoods like ours where men are so underserved need a place like this," says Bruce Armstrong, DSW, the clinic's founder and director. "Our goal is to interject reproductive health at every visit and help these young men communicate with their partners about birth control and condoms."

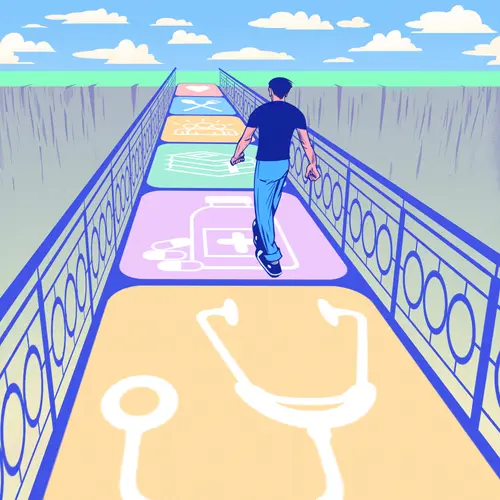

When it comes to reproductive health, adolescents and young men often seem to be left out of the equation. Of the five million patients served by the nation's 4,600 federally-funded family planning clinics, only about 3% are men, according to the federal Office of Family Planning. Recent studies, however, suggest that young men want to be involved in reproductive health issues. For instance, data from a national survey of 2,526 men ages 20 to 39 found that at least two-thirds viewed decisions about sex and contraception as shared responsibilities and nearly 90% felt that way about having children, according to a September/October 1996 report in the journal Family Planning Perspectives.

Unfortunately, young men don't know where to turn for help. Unlike women, who need to visit a doctor to get the pill or a diaphragm, guys can get condoms without seeing a health care provider. Yet many teenage boys consider themselves too old for the pediatrician and too young for the internist. As a result, guys haven't gotten the message that they can and should take reproductive responsibility in their relationships.

Recent federal programs hope to reverse this situation. Under the umbrella of the Clinton administration's Fatherhood Initiative, the Office of Family Planning has awarded grants totaling $4.7 million to 24 community-based organizations to develop and test approaches for delivering reproductive health services to young men.

The clinic at Columbia is one recipient of such a grant. Director Bruce Armstrong, PhD, casually dressed in a cotton shirt, khaki slacks, and boat shoes, earned his doctorate in social work. In 1986, he started his program to offer sports and job-related physicals to neighborhood boys. Once the guys got in the door, Armstrong and his staff used the opportunity to educate them about other health needs: the proper way to put on a condom, the signs and symptoms of various STDs.

Today, medical director David Bell, MD, an adolescent medicine specialist, supervises 10 medical students and two doctors, furthering Armstrong's goal of training future doctors in the care of young men. They work out of a women's clinic that becomes the Young Men's Clinic on Monday evenings and Friday afternoons -- and they take advantage of being based in a place where women get care. Clinic coordinator Darren Petillo visits women while they're in the waiting room, describes the men's program and asks the women if they'll ask their boyfriends to come in. The approach works: 50% of the clinic's new male patients are referred by women, twice the rate of two years ago. "Everything we do is strategically thought out," says Armstrong.

On a recent Monday night, medical students were picking up charts, escorting patients into private rooms, interviewing them about medical problems and lifestyle concerns, and passing the charts on to the doctors. On this evening they will see 26 patients, including a 17-year-old who came for a routine physical but complained of back spasms, and a 15-year-old who needed a physical for his school basketball team.

"He describes himself as being in excellent health, but you'll still do your history," Armstrong tells the students about the young basketball player. "Find out if he has a partner he's getting close to." Another young man who lost his job recently says he'd been smoking more marijuana than usual. He ultimately sees the in-house social worker, who helps him make the connection between his pot use and the stress from losing his job.

In one of the exam rooms, Felix (not his real name), 25, tells Bell that his girlfriend was diagnosed with chlamydia earlier that day. They both were treated previously but because they didn't take their medication at the same time, the infection kept bouncing back and forth between them.

Although he'd seen Felix recently, Bell updates his medical history. "How many partners have you had in the last three months?" he asks.

"Three," Felix replies.

"Have you ever had sex with a guy?" Felix shakes his head no.

"Did you use a condom the last time you had sex?" His girlfriend was using contraception, Felix explains in broken English, "but she stopped because we want to have a child right now."

Bell continues: "Have you ever hit a partner? Have you ever been hit by a partner?" No to both.

"Have you ever had oral sex?" Yes. "Have you ever had anal sex?" No. After examining Felix, Bell reviews the ABCs of STDs, including a discussion of HIV and AIDS. "Any questions?" he asks.

"When you have HIV, you're gonna die?" Felix asks.

Bell explains that infection with HIV is not the same as AIDS, but that new medicines are transforming HIV infection from a possible death sentence when it transforms into AIDS into a chronic and manageable disease. Sensing Felix's anxiety, he asks him if he wants to be tested for HIV.

"Si," Felix replies.

"Do you want to ask or tell me anything in Spanish?" Bell asks. Felix nods. An interpreter enters the room and Bell goes through the informed consent process, making sure to answer Felix's questions.

Before Felix leaves, Bell explains when he should follow up to get his HIV test results and hands him a bottle containing four antibiotic pills, which he is to take all at once. "Your girlfriend takes hers today and in a few days it will all be gone," the doctor says reassuringly.

Bell spent about 30 minutes with his patient. Had he rushed the process he would not have been able to counsel Felix about risky sexual behavior or to learn that his larger concern was HIV. In this kind of interaction, Armstrong believes there are tremendous opportunities for medical students to learn -- and to serve patients.

Toward that goal, Bell recruits graduate students in public health to develop fliers and educational brochures, such as the one titled "Talkin' to Your Girl about Sex & Health." As a result of this outreach, the clinic will serve 2,000 young men this year, up from 1,200 about a year ago. Patients pay on a sliding scale. Armstrong will not turn away people who can't pay or have no insurance, so money is always tight.

This shows in the reception area, where Rodrigue has been waiting for three hours to see a doctor. He says he doesn't mind, though. "I'm doing this for myself - and her," he says about his girlfriend, who accompanies him.

"I'm not nervous about the exam," he goes on. "If you don't take care of yourself, anything can happen. I know. One of my sisters has HIV."

Rodrigue says the neighborhood needs a clinic like this. "These young teenagers, they're wild these days," he says, sounding more mature than his years. "A lot of guys don't know about condom effectiveness or that pre-ejaculate can get a girl pregnant. They don't want to look stupid, so they don't ask questions."

He says he likes the way the staff treats him. "I think the people here are bold, dealing with guys with all sorts of attitudes."

Armstrong beams at the compliment. "These are guys I respect a lot," he says. "It's important for them to know they have a medical home."