What Is Graves' Disease?

Graves’ disease is an autoimmune condition that causes your thyroid to become hyperactive -- work harder than it needs to. It is one of the most common thyroid problems and the leading cause of hyperthyroidism, a condition in which the thyroid gland produces too many hormones. It was named after the man who first described it in the early 19th century, Sir Robert Graves.

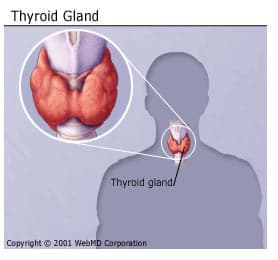

The thyroid gland is a small butterfly-shaped gland that sits in the front of your neck and releases hormones that help regulate your metabolism. When you have Graves’ disease, your immune system attacks your thyroid, causing it to overproduce those hormones, which causes a number of problems in different parts of your body. It usually affects people between the ages of 30 and 50 and is more common in women.

Once the disorder has been correctly diagnosed, it is quite easy to treat. In some cases, Graves' disease goes into remission or disappears completely after several months or years. Left untreated, however, it can lead to serious complications -- even death.

Causes of Graves' Disease

Hormones secreted by the thyroid gland control metabolism, or the speed at which the body converts food into energy. Metabolism is directly linked to the amount of hormones that circulate in the bloodstream. If, for some reason, the thyroid gland secretes too much of these hormones, the body's metabolism kicks into high gear, causing a pounding heart, sweating, trembling, and weight loss.

Normally, the thyroid gets its production orders through another chemical called thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), released by the pituitary gland in the brain. But in Graves' disease, a malfunction in the body's immune system releases abnormal antibodies that act like TSH. Spurred by these false signals to produce, the thyroid's hormone factories work overtime and overproduce.

Exactly why the immune system begins to produce these troublesome antibodies isn’t clear. Heredity and other characteristics seem to play a role. Studies show, for example, that if one identical twin contracts Graves' disease, there is a 20% likelihood that the other twin will get it too. Also, women are more likely than men to develop the disease. And smokers who develop Graves' disease are more prone to eye problems than nonsmokers with the disease. No single gene causes Graves’ disease. It is thought to be triggered by both genetics and environmental factors.

Symptoms of Graves’ Disease

The most common symptoms of Graves’ are symptoms of hyperthyroidism, which include:

Nervousness, anxiety or irritability

Tired or weak muscles

Shaking in your hands

Frequent bowel movements or diarrhea

Difficulty sleeping

Greater sensitivity to heat or increase sweating

Unintentional weight loss

An enlarged thyroid (also called a goiter)

A fast or irregular heartbeat

Changes in your period for women

Erectile dysfunction in men

Loss of sex drive (low libido)

Complications of Graves’ Disease

Eye complications

A small percentage of all Graves' patients will develop a condition called thyroid eye disease in which your eye muscles and tissues become swollen. This can cause exophthalmos -- your eyeballs protrude from their sockets -- and is considered a hallmark of Graves' disease, even though it’s rare. But having this complication doesn’t have anything to do with how severe your Graves’ disease is. In fact, it isn't clear whether such eye complications stem from Graves' disease itself or from a totally separate, but closely linked, disorder. If you have developed thyroid eye diease, your eyes may ache and feel dry and irritated. Protruding eyeballs are prone to excessive tearing and redness, partly because the eyelids can’t protect them as well.

In severe cases of exophthalmos, which are rare, swollen eye muscles can put tremendous pressure on the optic nerve, possibly leading to partial blindness. Eye muscles weakened by long periods of inflammation can lose their ability to control movement, resulting in double vision.

Skin complications

Some people with Graves’ may develop a rare skin condition known as pretibial myxedema or Graves’ dermopathy. It is a lumpy reddish thickening of the skin on the shins. It is usually painless and is not serious. Like exophthalmos this condition does not necessarily begin with the onset of Graves' and doesn’t have to do with how severe your disease is.

Graves’ Disease Diagnosis

If you have symptoms or signs of the complications of Graves’ disease, your doctor will probably ask you if you have a family history of the condition and order one or more of the following tests:

A blood test to check your levels of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) and other thyroid hormones. With Graves’ disease your TSH levels are usually suppressed and your other hormones are elevated.

Lab tests to look for the antibodies that cause Graves’s disease. If you don’t have them, that’s a sign that your hyperthyroidism is caused by something else.

A radioactive iodine uptake test that uses small doses of radioactive iodine to watch how much of it is taken up into your thyroid from your bloodstream. Your body normally uses iodine to make thyroid hormones, so if it takes in a lot of the radioactive iodine it is a sign that it is working harder than it needs to.

A thyroid scan to see where the radioactive iodine travels in your thyroid gland. If it goes all over your thyroid, that suggests you have Graves’ disease, because with other causes of hypothyroidism, only some parts of the gland are involved.

Grave’s Disease Treatment

There are two goals in the treatment for Graves’ disease. One is to stop your thyroid gland from overproducing thyroid hormone. The other is to stop the increased levels of thyroid hormone from causing problems in your body. There are a number of treatment options to achieve one or both of these goals.

Radioactive iodine therapy

With this treatment, you take another form of radioactive iodine by mouth than what is used in the test to diagnose Graves’ disease. The iodine gets into your thyroid and the radiation kills some of the cells in your thyroid that are overproducing thyroid hormones. It’s possible that this treatment could make any eye problems you have from Graves’ disease temporarily worse and it’s also likely it will lead to a lower production of thyroid hormone than is healthy. If that happens, your low thyroid can be treated. Because this treatment uses radiation, it’s not used on pregnant or breastfeeding women.

Medications

Anti-thyroid medications make your thyroid produce less thyroid hormone. They aren’t permanent treatments but can be used for long periods of time and sometimes help even after you’ve stopped treatment. They’re usually the treatment of choice for pregnant or breastfeeding women who can’t be exposed to radiation. They’re also sometimes used in combination with radioactive iodine therapy.

Beta blockersare medications typically used to reduce blood pressure, and they can help rapidly relieve some of the symptoms of hyperthyroidism including shaking, rapid heartbeat, and anxiety.

Surgery is a less common treatment for Graves’ disease but may be a good choice if you have a goiter or you’re pregnant and can’t take anti-thyroid medications. During surgery, some or all of your thyroid gland is removed. After surgery, you may need to take a daily thyroid medication for the rest of your life.

Although the symptoms can cause discomfort, Graves' disease generally has no long-term adverse health consequences if you get prompt and proper medical care.