Examining Moral Injury in Medicine

Hide Video Transcript

Video Transcript

[AUDIO LOGO]

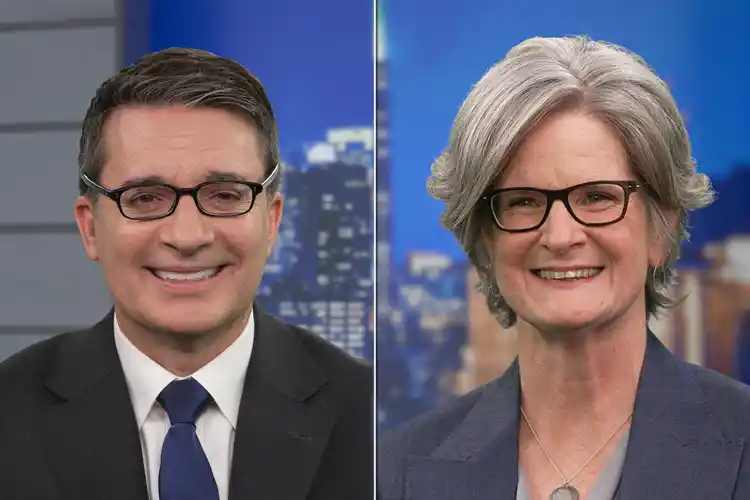

Dr. Wendy Dean is the co-founder of Moral Injury of Healthcare. She has a new book out, If I betray These Words, where she interviews physicians who talk about how they feel trapped between the patient-first values of their Hippocratic oath and the business imperatives of a broken health system. Wendy, thanks for joining me.

What we're realizing is that as medicine has become more corporatized, our voices as physicians matter less and less. It's starting to become more and more about what administrators need, what the business of health care needs. Now, when I say that, I don't intend to mean that anyone has ill intent when they go into this. But it's almost as though the structure has taken on a life of its own.

[LAUGHTER]

JOHN WHYTE

Physician burnout is a topic that we've covered quite a bit on WebMD and Medscape. It doesn't just impact the physician. It also impacts his or her family, the institution for which they work, as well as the entire health ecosystem. It's a problem that started before the pandemic, but certainly has been exacerbated by it. So what do we need to do to fix it? How do we make it better? My guest today may have the solution. Dr. Wendy Dean is the co-founder of Moral Injury of Healthcare. She has a new book out, If I betray These Words, where she interviews physicians who talk about how they feel trapped between the patient-first values of their Hippocratic oath and the business imperatives of a broken health system. Wendy, thanks for joining me.

WENDY DEAN

Thank you. It's such a pleasure to be here. JOHN WHYTE

I loved your new book. And what I want to ask you first is, we talk about burnout, but you talk about this concept of moral injury. And I have to say, that sounds pretty serious, moral and injury, right? So I want to ask you if you can tease out what you're talking about. WENDY DEAN

So moral injury is this sense that clinicians have they know what their patients need, and they cannot get it for them because of constraints outside of their control. And what that does is it causes us to wonder whether we can be the doctors that we thought we could be. So it's this sense that we made a promise to society that we would heal and that we would put our patients before all else. And yet as soon as we go out into practice, we realize that there are so many barriers in the way between what we know we should do and what we're able to do. What we're realizing is that as medicine has become more corporatized, our voices as physicians matter less and less. It's starting to become more and more about what administrators need, what the business of health care needs. Now, when I say that, I don't intend to mean that anyone has ill intent when they go into this. But it's almost as though the structure has taken on a life of its own.

JOHN WHYTE

But are the values misaligned? So what you're trying to do as a health professional may be different than what a health executive is doing and what actually then a patient wants. Is that the root cause of it? WENDY DEAN

We are getting to a point where we're not talking to each other anymore, which means that we're not making sure that our values are all aligned. And the executives are trying to keep the healthcare system alive. Physicians are trying to keep patients alive in alignment with their values. And those sets of values don't always overlap. So, yes. JOHN WHYTE

And the moral injury is not just for physicians. We should be clear. You and I are physicians. We're talking about it from the perspective of physicians. But correct me if I'm wrong, it's also the same in terms of moral injury as it relates to nursing, as it relates to pharmacy, as it relates to the entire health ecosystem. Tell us how it's impacting those health professionals. WENDY DEAN

They have come to us and said the same thing that this is our language too. From social work to physical therapists to nurses, they are all feeling the same pressure. And in fact, there is newly emerging research that shows that administrators feel it too. 40% of administrators during the pandemic acknowledged some level of moral injury. So it is a system-wide challenge. JOHN WHYTE

Your subtitle in the book is "Moral Injury in Medicine and Why it's so Hard for Clinicians to Put Patients First." But when we're talking about moral injury, we're talking about the clinicians too in what's important to them and how they do their job, but also have balance with their lives. So how do you do both? You want to put the patient first, right? But you also have to be cognizant of your own abilities, your own time constraints, the importance of social interactions and family and being able, sometimes, to tune out. How do you do both? WENDY DEAN

So I think the way to do both is to have systems that work better. Because we all want to put our patients first, and the reason that we can't is we're distracted by systems challenges. If we make our systems better, and we take away those barriers between what we know we want to do and actually accomplishing it, I think we could smooth that balance. JOHN WHYTE

What's it doing to the clinician? We've seen incidences increase in physician-assisted suicide, in substance abuse. Talk to us about what you've learned is the impact on clinicians. WENDY DEAN

The impact on clinicians is devastating. And it's not just those horrible, tragic outcomes. It's also the everyday clinician who goes to work and is heartbroken at not being able to ease their patient's suffering, to heal them. They are frustrated every day not being able to get through the EMR, missing messages from their patients, not being able to get the prior authorization quickly enough to get treatment started. Not being able to talk to their colleagues about a difficult case because they don't have the time. They're fighting the systems and not being able to coordinate. JOHN WHYTE

Do people think they're alone? Because others could say, you know what? They're having the challenges, but maybe it seems like there's a bunch of other colleagues who are doing fine and managing it all. Do we see differences in specialty or type of practice? Because one could also say this concept of imposter syndrome then start to think, you know what? Maybe this isn't the profession for me. Maybe I can't really manage and thrive in it. And we have to help them understand it's not their fault. It's the system. So the discussions are important to get this out in the open, isn't it? WENDY DEAN

It's really important. And that's why we wrote the book. We realized that a psychiatrist and a plastic surgeon on opposite ends-- arguably on opposite ends of the specialty spectrum had had the same experience of trying to work in health care. That's how we came together and started looking for this new language to say, this is something different. And I have worked with folks across the spectrum. You wouldn't think orthopedic surgeons were suffering moral injury. But I cannot tell you how many of them have come to me and said, this is my challenge. I want to go back to taking care of patients. JOHN WHYTE

But what's the one or two things that you would tell viewers that we need to start doing right away? WENDY DEAN

I think I alluded to it before. And one of them is to start breaking down the barriers that have been artificially constructed between administrators and clinicians to start being curious about what the other's challenges are. JOHN WHYTE

How do we break down those barriers, though? WENDY DEAN

Be curious, ask questions, invite administrators to shadow in clinic. Likewise, if physicians or clinicians are invited into administrative spaces, go-- accept that offer. So I think that's the very first thing is to get curious about what our challenges are on either end. The other is to start speaking with our colleagues either across licensee groups and within licensee groups to understand that this isn't just our challenge alone. JOHN WHYTE

Should we stop using the word "burnout" and instead use "moral injury"? WENDY DEAN

I don't think so. I think it's both. And I think there are absolutely systems problems that lead to a demand resource mismatch of burnout. But there's also this other sort of existential threat to our profession that is exemplified in moral injury that we really need to address as well. JOHN WHYTE

I always like to ask authors, when they write a book what surprised them, either about the content or about themselves in the writing process. WENDY DEAN

Everybody says writing a book is hard. Writing stories-- finding stories and telling them well is really, really hard. So my hat is off to writers who do that every day. JOHN WHYTE

What's your favorite story? Give us a sneak peek. [LAUGHTER]

WENDY DEAN

Oh, boy. Chapter 7 is great. About this really remarkable US Army veteran who took care of service members in Iraq and came back to take care of her neighbors in a small town in the Midwest, and how she stood up for what she believed in. JOHN WHYTE

Wow. Where can people find your book? WENDY DEAN

Almost everywhere-- favorite bookstores, Barnes & Noble online, Amazon online, or at our website, fixmoralinjury.org. JOHN WHYTE

Dr. Wendy Dean, thanks for taking the time today and for raising this issue and talking about how the healthcare system needs to change to prevent further injury. WENDY DEAN

Thank you so much. [AUDIO LOGO]