Snakebites: What You Need to Know

Rare, But Serious

Snakebites aren’t very common in the U.S., even for people who spend a lot of time outdoors. And most snakes in North America aren’t venomous, meaning you don’t get poison from them if they do bite. You’re much more likely to get struck by lightning than die from one. Still, it’s best to avoid them and to treat any bite as a medical emergency.

Treatment: First Aid

If you’ve been bitten by a snake, get medical help right away. To help someone with a snakebite:

- Take off all jewelry and tight clothing to avoid problems with swelling.

- Keep the area of the bite below the heart to keep venom from spreading.

- Keep the person as still as possible to keep venom from spreading.

- Cover the bite loosely with a clean, dry bandage.

- Help the person stay calm to prevent shock.

What Not to Do

When treating a snakebite:

- Don’t try to pick up or kill the snake. Even dead snakes have been known to bite.

- Don’t tightly wrap the bite area. Use only a loose bandage.

- Don’t cut across the area of the bite or try to suck the venom out.

- Don’t drink alcohol or anything with caffeine. They make your body take in the venom faster.

- Don’t use any ointments, chemicals, heat, cold, or ice.

- Don’t take aspirin -- it can make bleeding worse.

Treatment: Antivenom

This is the only way to treat venomous snakebites. It’s best to get antivenom within 4 hours of the bite, but it can still help if you get it within 24 hours. You get it through an IV -- the medicine goes into a vein through a needle. It drips in slowly to make sure you don’t have a reaction.

Which Are Most Dangerous?

Rattlesnakes are the kind most likely to bite you in the U.S., and almost all the deaths reported are from them. There are a lot of rattlesnakes, and they have a strong venom. The eastern diamondback rattlesnake's venom is the most toxic. Copperheads cause the second most bites and have a weak venom. Cottonmouths are next as far as number of bites, and they have a medium-strong venom. Coral snake bites are rare, but their venom is deadly.

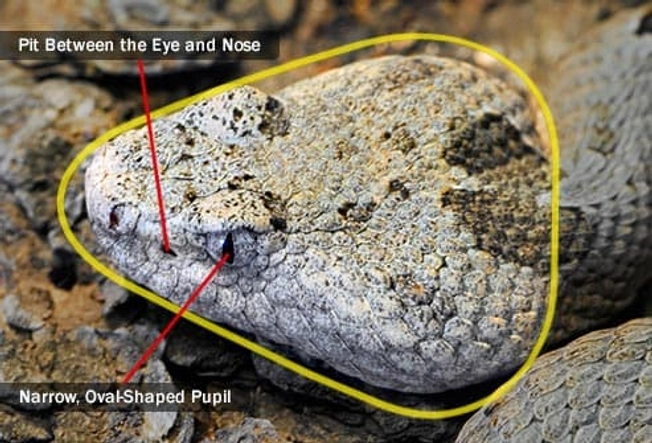

Pit Vipers

Rattlesnakes, copperheads, and cottonmouths are in this family. They have:

- A pit between the eye and nose on each side of the head

- Long, hollow fangs that fold back into their mouths

- Narrow, oval-shaped pupils in their eyes, like cats

- Triangle-shaped heads

Pit Viper Bite Symptoms

These depend on your age and body size, as well as the type of snake, where you got bit, how many bites there were, and how much venom went in. Signs of pit viper bites include:

- Fang puncture marks -- typically two very clear marks, maybe along with scratches or marks from smaller teeth

- Bruising

- Serious pain

- Oozing from the bite mark

- Swelling within 5 minutes

- Throwing up

- Weakness

Pit Viper Venom

This isn’t deadly right away unless it happens to go directly into a vein. But it will start to break down tissue and blood vessels, and that can lead to fluid buildup, bleeding inside your body, and serious problems like kidney failure.

Pit Vipers: Rattlesnakes

There are many different kinds of these across the mountains, prairies, deserts, and beaches of the U.S. They’re also found in Mexico and a few pockets of Canada. They can have different colors and markings, which can include ovals, diamonds, or rings. Their most obvious feature is the rattle sound they make by shaking their tail -- a warning to other creatures to stay away.

Pit Vipers: Cottonmouths

Also called water moccasins, these snakes live in and around ponds, marshes, rivers, and other waterways in the southeastern U.S. They’re dark in color, from dark tan to almost totally black, and they have dark bands that may be hard to see. Their mouths have a white, cottony lining, which is how they got their name.

Pit Vipers: Copperheads

These snakes typically live in forests, rocky areas, and around water, though you might also stumble across one in a vacant lot. They live mostly in the eastern U.S., though they’re spread as far west as Texas. They’re also found in Mexico. They typically have tan bodies with brown or reddish-brown bands in the shape of an hourglass. They’re not very aggressive and tend to freeze when they’re scared.

Coral Snakes

These venomous snakes have short fangs and strike down, then chew, when they attack. They have rings of color in a repeating black, yellow, red, yellow pattern. Some harmless snakes have colors like that, but their red and yellow rings don’t touch. Remember this saying: "Red on yellow, kill a fellow. Red on black, venom lack." They’re found in woody, sandy, or marshy areas of the southern U.S.

Coral Snake Bite Symptoms

These bites may not leave much of a mark or cause any swelling, and you may not feel any pain. You might not have any symptoms for many hours. When they do show up, they can include:

- Anxiety

- Blurred or double vision

- General feeling of sickness

- A lot more saliva than usual

- Nausea, throwing up, and stomach pain

- Sleepiness

- Slurred speech

- Sweating

Coral Snake Venom

Venom from coral snakes attacks tissue in your nervous system. Your muscles may get weak, and eventually you may not be able to move them. It can also paralyze the muscles that control your heart and lungs. If it’s not treated in time, one of these bites can be deadly.

Why Snakes Bite

Usually, they only attack when it’s dinnertime or when they need to defend themselves. They’re typically more interested in getting away from people than attacking them. The danger is when the snake is startled or threatened. Venomous snakes can control how much venom they give you. Sometimes, they bite but don’t put out any venom at all.

How to Prevent Snakebites

You can do things to try to avoid them:

- Wear shoes outside.

- Don’t camp near swamps, streams, or other places snakes live.

- Don’t stick your hands into places you can’t see, like in between rocks.

- If you see a snake, slowly back away.

- Keep the grass around your house cut low.

- Never try to catch or pick up a snake.

- Keep piles of wood, rocks, or other debris away from your house -- snakes, and the animals they eat, can hide there.