What Is Lyme Disease?

Lyme disease is a bacterial infection caused by Borrelia burgdorferi and, rarely, Borrelia mayonii bacteria.

What kind of ticks carry Lyme disease?

Infected backlegged ticks (also called deer ticks) can transmit the bacteria when they bite. The bacteria then travel through your bloodstream. When not treated early, the infection can turn into an inflammatory condition that affects multiple parts of your body, including the skin, joints, and nervous system.

How small are the ticks?

Ticks come in three sizes depending on their stage of life. They can be the size of a grain of sand, a poppy seed, or an apple seed.

What are my chances of getting Lyme disease?

The chances you might get Lyme disease from a tick bite depend on the kind of tick, where you were when it bit you, and how long it was attached. You’re more likely to get Lyme disease if you live in the Northeastern United States. The upper Midwest is also a hot spot. But it affects people in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. The chance of infection is higher the longer an infected tick stays attached, around 36-48 hours.

Which areas are more likely to have Lyme disease?

The tick that causes Lyme disease has been moving from the Northeast and upper Midwest into the Southern and Western U.S., Mexico, and Canada.

According to the CDC, the states with the most reported cases in 2020 were Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, Wisconsin, and Maine.

In the Southern U.S., where it’s hotter, ticks stay under leaves so they don't dry out. This means people in the South don’t get Lyme from ticks very often because the ticks don't usually come out to bite.

Even though people only report about 30,000 cases of Lyme infection in the U.S. each year, there are actually around 476,000 a year. The same tick also can spread other diseases, including babesiosis, anaplasmosis, and Powassan virus. Those diseases are also on the rise in the U.S.

Who is most likely to get Lyme disease?

Boys up to age 15 and men between the ages of 40 and 60 are more likely to get Lyme disease. The reasons for that aren't clear, but it might be because those groups may be more likely to spend time outside.

Why are there more ticks now than there used to be?

There are several reasons why Lyme is spreading. Some of these are:

- New trees being planted, especially in the Northeastern U.S.

- Climate change and very hot or cold temperatures

- People moving away from large cities

- More contact with white-tailed deer (the blacklegged tick's favorite way to travel)

In the last century, many trees were cut down to make way for buildings. That led to a drop in the deer population. But in the past few decades, people have planted more trees, so both the deer and tick populations have grown.

Deer and white-footed mice give Lyme disease to ticks that bite them. As their habitats shrink, they live closer to people. Dogs also carry ticks into homes and spread them to their humans.

As the climate warms, some people spend more time outside. That raises the odds of being bitten, particularly in areas where Lyme disease is common. That doesn't mean you should avoid outdoor activities. But take steps prevent tick bites and check for them, just in case.

Lyme Disease Symptoms

In most Lyme infections, one of the first symptoms you’ll notice is a rash. Symptoms can start anywhere from 3 to 30 days after the bite. They may look different depending on your stage of infection. In some cases, you won’t notice any until months after the bite.

Early symptoms include:

- Fever

- Chills

- Headache

- Fatigue

- Muscle and joint pain

- Swollen lymph nodes

Lyme disease rash

Some Lyme rashes look like a bull's-eye with circles around the middle. But most are round, red, and at least 2 inches across. The rash slowly gets bigger over several days. It can grow to about 12 inches across. It may feel warm to the touch, but it’s usually not itchy or painful. It can show up on any part of your body.

The rash may not look as red on darker skin tones or stand out as much as it does on lighter skin. This can make it hard to spot. Research suggests that how the rash appears on different skin types can lead to late diagnosis. And early diagnosis is critical -- Lyme disease can lead to severe problems when left untreated.

Without treatment, symptoms can get worse. They might include:

- Severe headache or neck stiffness

- Rashes on other areas of your body

- Arthritis with joint pain and swelling, particularly in your knees

- Drooping on one or both sides of your face

- An irregular heartbeat

- Inflammation in your brain and spinal cord

- Shooting pains, numbness, or tingling in your hands or feet

You could also form neurologic Lyme disease. That's when symptoms affect your peripheral or central nervous systems. This tends to happen most in early disseminated Lyme disease (more on the different types later). Signs include:

- Numbness

- Pain

- Facial palsy (or facial droop)

- Weakness

- Meningitis symptoms (fever, severe headache, or stiff neck)

- Visual issues

Lyme Disease Diagnosis

The doctor will diagnose you based on your symptoms and whether you’ve been exposed to ticks. You may also get a blood test. The test may come back negative the first few weeks of infection because antibodies take a while to show up. It may take 4-6 weeks to see a positive result.

Lyme disease test

The CDC suggests your doctor do a two-step Lyme disease test. They'll be able to use the same blood sample for both tests. If the first step is negative, you won't have to do the second one. But if the first test is positive or indeterminate/equivocal (which means it's not negative or positive), your doctor will do a second test. If both results are positive (or indeterminate/equivocal) then your overall Lyme disease diagnosis is positive.

There are also at-home Lyme disease tests. You prick your finger to collect a drop of blood then send it to a lab. Not all at-home tests are accurate, so it's important to see your doctor if you test yourself.

Is Lyme disease contagious?

You can't get Lyme disease from touching, kissing, or having sex with someone who has it. If untreated, it's possible to pass the disease to your unborn baby through the placenta, but this is rare.

What Are the Stages of Lyme Disease?

There are three stages of Lyme disease:

Early localized Lyme

Flu-like symptoms such as fever, chills, headache, swollen lymph nodes, sore throat, and a rash that looks like a bull's-eye or is round and red and at least 2 inches long. This stage typically starts 3-30 days after a tick bite.

Early disseminated Lyme

Flu-like symptoms such as pain, weakness, or numbness in your arms and legs, changes in your vision, heart palpitations and chest pain, a rash (that may nor may not be a bull’s-eye rash), and a type of facial paralysis known as Bell’s palsy.

Late disseminated Lyme

This can happen weeks, months, or years after the tick bite. Symptoms may include arthritis, severe fatigue and headaches, dizziness, trouble sleeping, and confusion.

About 10% of people treated for Lyme infection don’t shake the disease. This Lyme disease complication can create symptoms that last longer than others. They may go on to have three core symptoms: joint or muscle pain, fatigue, and short-term memory loss or confusion. This is called post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome (PTLDS). It can be hard to diagnose because it has the same symptoms as other diseases and there isn't a blood test to confirm it. Some people also call this chronic Lyme disease (CLD). But this name can refer to many different illnesses within Lyme disease, which can cause confusion. Because of this, doctors don't use this name often.

Experts aren’t sure why Lyme symptoms don’t always go away. One theory is that your body keeps fighting the infection even after the bacteria are gone, like an autoimmune disorder.

Lyme Disease Treatment

With early-stage Lyme disease, you’ll take antibiotics for about 10 days to 3 weeks. The most common ones are amoxicillin, cefuroxime, and doxycycline. The antibiotics will almost always cure your infection. If they don’t, you might get other antibiotics either by mouth or as a shot.

If you don’t treat your Lyme infection, you might need oral antibiotics for symptoms like weakened face muscles and irregular heartbeat. You may need antibiotics if you have meningitis, inflammation in your brain and spinal cord, or more severe heart problems.

If your Lyme is late stage, the doctor might give you antibiotics either by mouth or as a shot. If it causes arthritis, you’ll get arthritis treatment.

There are no treatments for post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome.

Is Lyme disease curable?

Yes. If you take the right antibiotics early on in the disease, you'll usually get better quickly.

What's the Best Way to Prevent a Tick Bite?

Ticks can't fly or jump. But they live in shrubs and bushes and can grab onto you when you pass by. To avoid getting bitten:

- Wear pants and socks in areas with lots of trees and when you touch fallen leaves.

- Wear a tick repellent on your skin and clothing that has DEET, lemon oil, or eucalyptus.

- For even more protection, use the chemical permethrin on clothing and camping gear.

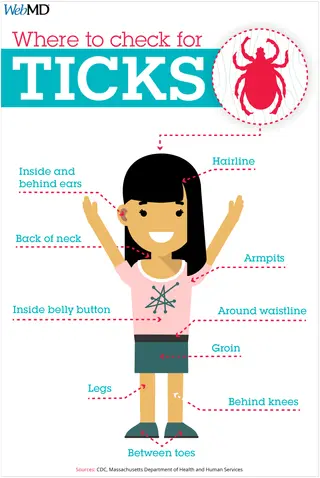

- Shower within 2 hours after coming inside. Look for ticks on your skin, and wash ticks out of your hair.

- Put your clothing and any exposed gear into a hot dryer to kill whatever pests might be on them.

How do you know if you've been bitten?

Ticks are small, so you've got to have pretty good eyes to see them.

If you have a small, reddish bump on your skin that looks like a mosquito bite, it could be a tick bite. If it goes away in a few days, it’s not a problem. Remember, a tick bite doesn’t necessarily mean you have Lyme disease.

If you notice a rash in the shape of a bull's-eye, you might have a tick bite. Talk to your doctor about treatment.

If you have an allergic reaction to ticks, you'll notice a bite right away.

What Should You Do If There's a Tick Under Your Skin?

You probably won’t get infected if you remove the tick within 36-48 hours.

How do you throw away a tick?

Put it in soapy water or alcohol, stick it to a piece of tape, or flush it down the toilet.

When Should You See a Doctor If You Think You Have Lyme?

The rash is a pretty good indication that you may have been bitten. Take a photo of the rash and see your doctor. At this stage, treatment with antibiotics will probably work.

If you don't have the rash but have symptoms like fatigue, fever, and headache but no respiratory symptoms like a cough, you may want to talk to your doctor.

Lyme Disease Vaccine

In 2017, a French company called Valneva started testing a Lyme disease vaccine on adults in the U.S. and Europe. The vaccine is in the third and final phase of clinical trials.

Lyme Disease in Dogs

The more ticks in your region, the likelier it is that your furry pal will bring them home.

Can dogs get Lyme disease?

Your dog is much more likely to be bitten by a tick than you are. And where Lyme disease is common, up to 25% of dogs have had it at some point.

About 10% of dogs with Lyme disease will get sick 7-21 days after a tick bite.

Lyme disease symptoms in dogs

Your dog might seem like they’re walking on eggshells. They also might have a fever and enlarged lymph nodes. Plus, they might seem tired. Dogs also get antibiotics for Lyme.

What if my dog brings ticks into my home?

Use a tick control product on your pet to prevent Lyme disease.

Check your dog’s whole body each day for bumps. If you notice a swollen area, see if there’s a tick there. If you find a tick, wear gloves while you use tweezers to separate it from your dog. Then, put it in soapy water or alcohol, or flush it down the toilet.

Use alcohol to clean the spot on your dog where the tick was attached. Keep an eye on that spot and also on your dog to make sure they’re behaving normally. If you notice any changes, talk with your vet.

Lyme disease vaccine for dogs

Also, have your dog vaccinated against Lyme disease, especially if you live or travel to areas with Lyme disease. There are four types of Lyme disease vaccines approved for dogs. They're all safe and work well against the disease.

Takeaways

You get Lyme disease from bacteria transmitted through the bite of infected ticks, mostly deer ticks. These ticks can be as small as a grain of sand, and you'll commonly find them in wooded or grassy areas. Symptoms of Lyme disease can include fever, headache, fatigue, and a rash that may resemble a bull's-eye. If left untreated, the infection can lead to more serious problems affecting your joints, nervous system, and heart. Treatment typically involves antibiotics, but in some cases, symptoms may linger, leading to a condition known as post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome (PTLDS).