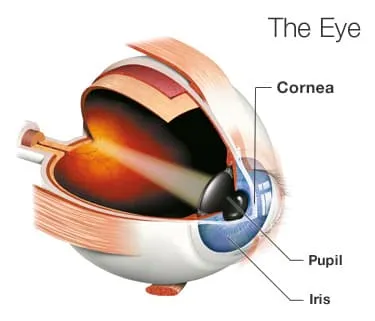

The cornea is the clear layer on the front of your eye that helps focus light so you can see clearly. If it gets damaged, you might need to have it replaced.

The surgeon will remove all or part of your cornea and replace it with a healthy layer of tissue. The new cornea comes from people who chose to donate this tissue when they died.

A cornea transplant, also called keratoplasty, can bring back vision, lessen pain, and possible improve the appearance of your cornea if it is white and scarred.

Who Needs One?

The light rays that pass through a damaged cornea can get distorted and change your vision.

A corneal transplant corrects several eye problems, including:

- Cornea scarring because of an injury or an infection

- Corneal ulcers or "sores" from an infection

- A medical condition that makes your cornea bulge out (keratoconus)

- Thinning, clouding, or swelling of the cornea

- Inherited eye diseases, such as Fuchs' dystrophy and others

- Problems caused by an earlier eye operation

Your doctor will let you know which specific procedure is best for your condition.

Full Thickness Corneal Transplant

If the doctor does a penetrating keratoplasty (PK), all the layers of your cornea get replaced. The surgeon sews the new cornea onto your eye with stitches thinner than hair.

You might need this procedure if you have a severe cornea injury or bad bulging and scarring.

It has the longest healing time.

Partial Thickness Corneal Transplant

During deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty (DALK), the surgeon injects air to lift off and separate the thin outside and thick middle layers of your cornea, then removes and replaces only those.

People with keratoconus or a corneal scar that hasn't affected the inner layers may have this done.

The healing time with this procedure is shorter than a full thickness transplant. Because your eye itself isn't opened up, it's unlikely the lens and iris could be damaged, and there's less chance of an infection inside your eye.

Endothelial Keratoplasty

About half of the people who need cornea transplants each year have a problem with the innermost layer of the cornea, the endothelium.

Doctors often do this type of surgery to help Fuchs' dystrophy and other medical conditions.

Descemet's stripping endothelial keratoplasty (DSEK or DSAEK) is the most common type of endothelial keratoplasty. The surgeon removes the endothelium -- a mere one cell thick -- and the Descemet membrane just above it. Then they replace them with a donated endothelium and Descemet membrane still attached to the stroma (the cornea's thick middle layer) to help him handle the new tissue without damaging it.

Another variation, Descemet's membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK), transplants just the endothelium and Descemet membrane -- no supporting stroma. The donor tissue is very thin and fragile, so it's harder to work with, but healing from this procedure is usually quicker and often, the end result vision may be slightly better.

A third option for selected people with Fuch's dystrophy is simple removal of the central part of the inner membrane without a transplant, if the surrounding cornea seems healthy enough to provide cells to fill in the removed area.

These surgeries are good options for people with cornea damage only in the inner layer because recovery is easier.

What's the Surgery Like?

Before your operation, your doctor will probably do an exam and some lab tests to check that you're in good general health. You may have to stop taking certain medicines, such as aspirin, a couple of weeks before the procedure.

Usually, you'll have to use antibiotic drops in your eye the day before your transplant to help prevent an infection.

Most of the time, these surgeries are done as outpatient procedures under local anesthesia. This means you'll be awake but woozy, the area is numb, and you'll be able to go home the same day.

Your doctor will do the entire surgery while looking through a microscope. It typically takes 30 minutes to an hour.

Recovery

Afterward, you'll probably wear an eye patch for at least a day, maybe 4, until the top layer of your cornea heals. Your eye will most likely be red and sensitive to light. It might hurt or feel sore for a few days, but some people don't feel any discomfort.

Your doctor will prescribe eye drops to bring down inflammation and lower the chances of infection. They may prescribe other medicines to help with pain. They'll want to check your eye the day after surgery, several times during the following couple of weeks, and then a few more times during the first year.

For transplant procedures such as DSEK and DMEK that use a gas bubble inside the eye to help position the transplanted tissue, the surgeon may ask you to lie flat sometimes during the day and sleep flat on your back at night for a few days.

You'll have to protect your eye from injury after your surgery. Follow your doctor's instructions carefully.

Your cornea doesn't get any blood, so it heals slowly. If you needed stitches, your doctor will take them out at the office a few months later.

Possible Complications

A corneal transplant is considered a fairly safe procedure, but it is surgery, so there are risks.

In about 1 out of every 10 transplants, the body's immune system attacks the donated tissue. This is called rejection. It can be reversed with eye drops most of the time. Because so little donor tissue is used for DSEK and especially DMEK, there's a much lower risk of rejection with these procedures.

Other things that could happen include:

- Infection

- Bleeding

- Higher pressure in the eye (called glaucoma)

- Clouding of the eye's lens (called cataracts)

- Swelling of the cornea

- A detached retina, when the back inside surface of your eye pulls away from its normal position

Results

Most people who have a cornea transplant get at least part of their vision restored, but each situation is different. It could take a few weeks and up to a year for your vision to improve fully. Your eyesight might get a little worse before it gets better.

Your glasses or contact lens prescription may need to be adjusted to include astigmatism correction because the transplanted tissue won't be perfectly round.

After the first year, you should see your eye doctor once or twice every year. The donated tissue usually lasts a lifetime.