At your regular eye exam, one thing your eye doctor always checks is your intraocular pressure. That's the pressure inside your eyes. It gives an important picture of your eye health and can find signs of optic nerve damage that might affect your sight.

Your eyes are filled with fluid that keeps them inflated like a ball. The normal pressure in the eyes can change during the day and differ from person to person. In healthy eyes, the fluids drain freely to keep eye pressure steady.

Ocular hypertension is when the pressure inside the eye is higher than normal. Eye pressure is measured in millimeters of mercury (mmHg). Normal eye pressure ranges from 10 to 21 mmHg. Ocular hypertension is an eye pressure of greater than 21 mmHg.

Ocular hypertension usually has these signs:

- An intraocular pressure of greater than 21 mmHg in one or both eyes at two or more office visits.

- The optic nerve appears normal.

- No signs of glaucoma are seen on visual field testing, which is a test to assess your peripheral (or side) vision.

- No signs of any eye disease are seen.

Ocular hypertension should not be considered a disease by itself. But if you have it, you may be more likely to develop glaucoma. As of 2022, an estimated 3 million people in the United States had glaucoma and more than 120,000 are legally blind because of this disease. These statistics emphasize the need to identify and closely monitor people who are at risk of developing glaucoma, particularly those with ocular hypertension.

Studies show that 3-6 million people in the United States, including 4%-10% of the population older than 40, have intraocular pressures of 21 mm Hg or higher. Studies over the last 20 years have helped to characterize those with ocular hypertension:

- They have an average estimated risk of 10% of developing glaucoma over 5 years. This risk may be decreased to 5% (a 50% decrease in risk) if eye pressure is lowered by medications or laser surgery. However, the risk may become even less than 1% per year because of significantly improved techniques for detecting glaucomatous damage. This could allow treatment to start much earlier, before vision loss occurs.

- Patients with thin corneas may be at a higher risk for glaucoma development. Therefore, your eye doctor might measure your corneal thickness.

- Over a 5-year period, the incidence of glaucomatous damage in people with ocular hypertension is about 2.6-3% for intraocular pressures of 21-25 mmHg, 12-26% for intraocular pressures of 26-30 mmHg, and approximately 42% for those higher than 30 mmHg.

- In approximately 3% of people with ocular hypertension, the veins in the retina can become blocked (called a retinal vein occlusion), which could lead to vision loss. Because of this, keeping pressures below 25 mmHg in people with ocular hypertension and who are older than age 65 is often suggested.

Some studies have found that the average intraocular pressure in Black and Hispanic people is higher than in white people, while other studies have found no difference.

- A 4-year study showed that African Americans with ocular hypertension were five times more likely to develop glaucoma than whites. Findings suggest that, on average, African Americans have thinner corneas, which may account for this increased likelihood to develop glaucoma, as a thinner cornea may cause pressure measurements in the office to be falsely low.

- In addition, African Americans are considered to have a three to four times greater risk of developing primary open-angle glaucoma. They are also believed to be more likely to have optic nerve damage.

Although some studies have reported a significantly higher average intraocular pressure in women than in men, other studies have not shown any difference between men and women.

- Some studies suggest that women could be at a higher risk for ocular hypertension, especially after menopause.

- Studies also show that men with ocular hypertension may be at a higher risk for glaucomatous damage.

Intraocular pressure slowly rises with increasing age, just as glaucoma becomes more prevalent as you get older.

- Being older than age 40 is a risk factor for both ocular hypertension and primary open-angle glaucoma.

- Elevated eye pressure in a young person is a cause for concern. A young person has a longer time to be exposed to high pressures over a lifetime and a greater likelihood of optic nerve damage.

Ocular Hypertension Causes

High pressure inside the eye is caused by an imbalance in the production and drainage of fluid in the eye. The channels that normally drain the fluid from inside the eye do not function correctly. More fluid is being made but cannot cannot drain. This results in an increased amount of fluid inside the eye, thus raising the pressure.

Another way to think of high pressure inside the eye is to imagine a water balloon. The more water that is put into the balloon, the higher the pressure inside the balloon. The same situation exists with too much fluid inside the eye: The more fluid, the higher the pressure. Also, just like a water balloon can burst if too much water is put into it, the optic nerve in the eye can be damaged by too high of a pressure.

People with very thick but normal corneas often have eye pressure measuring at the high levels of normal or even a little bit higher. Their pressures may actually be lower and normal, but the thick corneas cause a falsely high reading during measurements.

Ocular Hypertension Symptoms

Most people with ocular hypertension do not have any symptoms. For this reason, regular eye examinations with an eye doctor are very important to rule out any damage to the optic nerve from the high pressure.

Questions to Ask the Doctor

- Is my eye pressure elevated?

- Are there any signs of eye damage due to an injury?

- Has my optic nerve been damaged?

- Is my peripheral vision normal?

- Is treatment necessary?

- How often should I get follow-up examinations?

Exams and Tests

An eye doctor performs tests to measure intraocular pressure as well as to rule out early primary open-angle glaucoma or secondary causes of glaucoma.

- Your doctor checks your visual acuity, which refers to how well you can see an object, by having you read letters from across a room using an eye chart.

- The front of your eyes, including your cornea, anterior chamber, iris, and lens, are examined using a special microscope called a slit lamp.

- Your doctor will measure your eye pressure using a test called tonometry. Measurements are taken for both eyes on at least two or three occasions. Because intraocular pressure varies from hour to hour, measurements may be taken at different times of day (e.g., morning and night). A difference in pressure between the eyes of 3 mmHg or more may suggest glaucoma. Early primary open-angle glaucoma is very likely if the intraocular pressure is steadily increasing.

- Each optic nerve is examined for any damage or abnormalities. This may require dilation of your pupils. Pictures of your optic disk (the front surface of your optic nerve) are taken for future reference and comparison.

- A gonioscopy is performed to check the drainage angle of your eye. To do so, a special contact lens is placed on the eye. This test is important to determine if the angles are open, narrowed, or closed and to rule out any other conditions that could cause elevated intraocular pressure.

- Visual field testing checks your peripheral (or side) vision, typically by using an automated visual field machine. This test is done to rule out any visual field defects due to glaucoma. Visual field testing may need to be repeated. If there is a low risk of glaucomatous damage, then the test may be performed only once a year. If there is a high risk of glaucomatous damage, then the test may be performed as frequently as every 2 months.

- Pachymetry (or corneal thickness) is checked by an ultrasound probe to determine the accuracy of your intraocular pressure readings. A thinner cornea can give falsely low pressure readings, whereas a thick cornea can give falsely high pressure readings.

Ocular Hypertension Treatment Self-Care at Home

If your eye doctor prescribes medicines to help lower the pressure inside your eye, properly applying the medication and complying with your doctor’s instructions are very important. Not doing so could result in a further increase in intraocular pressure that can lead to optic nerve damage and permanent vision loss (from glaucoma).

Medical Treatment

The goal of medical treatment is to reduce the pressure before it causes glaucomatous loss of vision. Medical treatment is always started for people who are believed to be at the greatest risk for developing glaucoma and for those with signs of optic nerve damage.

How your eye doctor chooses to treat you is highly individualized. Depending on your particular situation, you may be treated with medications or just observed. Your doctor will discuss the pros and cons of medical treatment versus observation with you.

- Some eye doctors treat all elevated intraocular pressures of higher than 21 mmHg with topical medicines. Some do not medically treat unless there is evidence of optic nerve damage. Most eye doctors treat if pressures are consistently higher than 28-30 mmHg because of the high risk of optic nerve damage.

- If you have symptoms like halos, blurred vision, or pain, or if your intraocular pressure has recently increased and then continues to increase on subsequent visits, your eye doctor will most likely start medical treatment.

Your intraocular pressure is evaluated periodically using guidelines similar to these:

- If your intraocular pressure is 28 mmHg or higher, you are treated with medicines. After 1 month of taking the drug, you have a follow-up visit with your eye doctor to see if the medicine is lowering the pressure and there are no side effects. If the drug is working, then follow-up visits are scheduled every 3-4 months.

- If your intraocular pressure is 26-27 mmHg, the pressure is rechecked in 2-3 weeks after your initial visit, sometimes at a different time of day. On your second visit, if the pressure is still within 3 mmHg of the reading at the initial visit, then follow-up visits are scheduled every 3-4 months. If the pressure is lower on your second visit, then the length of time between follow-up visits is longer and is determined by your eye doctor. At least once a year, visual field testing is done and your optic nerve is examined.

- If your intraocular pressure is 22-25 mmHg, the pressure is rechecked in 2-3 months, sometimes at a different time of day. At the second visit, if the pressure is still within 3 mmHg of the reading at the initial visit, then your next visit is in 6 months and includes visual field testing and an optic nerve examination. Testing is repeated at least yearly.

Follow-up visits may also be scheduled for the following reasons:

- If a visual field defect shows up during a visual field test, repeat examinations are performed during future office visits. An eye doctor closely monitors a visual field defect because it may be a sign of early primary open-angle glaucoma. That is why it is important for you to do your best when taking the visual field test, as it may determine whether or not you have to start on medications to lower your eye pressure. If you get tired during a visual field test, make sure to tell the technician to pause the test so you can rest. That way, a more accurate visual field test can be obtained.

- A gonioscopy is performed at least once every 1-2 years if your intraocular pressure significantly increases or if you are being treated with miotics (a type of glaucoma medication).

- More pictures of the back of your eye are taken if the optic nerve/optic disk changes in appearance.

Medications

The ideal drug for treatment of ocular hypertension should effectively lower intraocular pressure, have no side effects, and be inexpensive with once-a-day dosing; however, no medicine possesses all of the above. When choosing a medicine for you, your eye doctor prioritizes these qualities based on your specific needs.

Medications, usually in the form of medicated eyedrops, are prescribed to help lower increased intraocular pressure. Sometimes, more than one medicine is needed.

Initially, your eye doctor might have you use the eyedrops in only one eye to see how effective the drug is in lowering the pressure inside your eye. If it is effective, then your doctor will most likely have you use the eyedrops in both eyes.

Once a medicine is prescribed, you have regular follow-up visits with your eye doctor. The first follow-up visit is usually 3-4 weeks after beginning the medicine. Your pressures are checked to ensure the drug is helping to lower your intraocular pressure. If the drug is working and is not causing any side effects, then it is continued and you are reevaluated 2-4 months later. If the drug is not helping to lower your intraocular pressure, then you will stop taking that drug and a new drug will be prescribed.

Your eye doctor may schedule your follow-up visits in accordance with the particular drug you are taking because some medicines may take 6-8 weeks to be fully effective.

During these follow-up visits, your eye doctor also observes you for any allergic reactions to the drug. If you are experiencing any side effects or symptoms while on the drug, be sure to tell your eye doctor.

Generally, if the pressure inside the eye cannot be lowered with medicines, you might have early primary open-angle glaucoma instead of ocular hypertension. In this case, your eye doctor will discuss the appropriate next steps in your treatment plan.

Surgery

Laser and surgical therapy are not generally used to treat ocular hypertension, because the risks associated with these therapies are higher than the actual risk of developing glaucomatous damage from ocular hypertension. However, if you cannot tolerate your eye medications, laser surgery could be an option, and you should discuss this therapy with your eye doctor.

Next Steps

Depending on the amount of optic nerve damage and the level of intraocular pressure control, people with ocular hypertension may need to be seen from every 2 months to yearly, even sooner if the pressures are not being adequately controlled.

Glaucoma should still be a concern in people who have elevated intraocular pressure with normal-looking optic nerves and normal visual field testing results or in people who have normal intraocular pressure with suspicious-looking optic nerves and visual field testing results. These people should be observed closely because they are at an increased risk for glaucoma.

Prevention

Ocular hypertension cannot be prevented, but through regular eye examinations with an eye doctor, its progression to glaucoma can be prevented.

Outlook

The prognosis is very good for people with ocular hypertension.

- With careful follow-up care and compliance with medical treatment, most people with ocular hypertension do not progress to primary open-angle glaucoma, and they retain good vision throughout their lifetime.

- With poor control of elevated intraocular pressure, continuing changes to the optic nerve and visual field that could lead to glaucoma might occur.

Multimedia

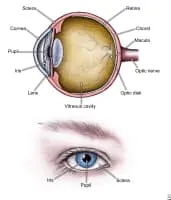

Media file 1: Parts of the eye.

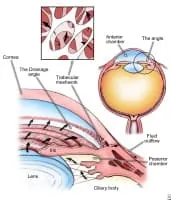

Media file 2: Elevated eye pressure is caused by a build-up of fluid inside the eye because the drainage channels (trabecular meshwork) cannot drain it properly. Elevated eye pressure can cause optic nerve damage and vision loss.