Cloning. More than ever, the word stirs emotion and triggers debate, as what was once science fiction becomes scientific fact. Just what are researchers working on and why? Do we have anything to gain, or to lose, from their continued efforts?

For the first time, researchers have successfully cloned a human embryo -- and have extracted stem cells, the body's building blocks, from the embryo. Stem cells are considered one of the greatest hopes for curing diseases like diabetes, Parkinson's disease, and paralysis caused by spinal cord injury.

What Is Cloning?

Before you decide where you stand on this debate, you'll need to understand where the science is today. To put it all in perspective, WebMD asked some renowned scientists to explain precisely what cloning is and what it isn't. Popular depictions -- from the ominous hordes of worker drones in the futuristic novel Brave New World to Michael Keaton's comic time-saving duplicates in the film Multiplicity -- have almost nothing to do with reality.

"Clones are genetically identical individuals," says Harry Griffin, PhD. "Twins are clones." Griffin is assistant director of the Roslin Institute -- the lab in Edinburgh, Scotland, where Dolly the cloned sheep was created in 1997.

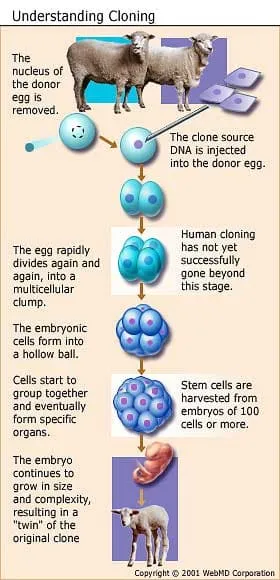

Usually, after sperm and egg meet, the fertilized cell begins dividing. Remaining in a clump, the one becomes two, then four, eight, 16, and so on. These cells become increasingly specialized to a particular function and organize into organs and systems. Eventually, it's a baby.

Sometimes, though, after the first division, the two cells split apart. They continue dividing separately, growing to become two individuals with the exact same genetic make-up -- identical twins, or clones. This phenomenon, though not entirely understood, is far from unusual. We've all known identical twins.

Early on, says Griffin, the term cloning referred to embryo splitting -- doing in the lab what happens in the woman's body to create identical twins. "It was first done in cattle, but there are one or two human examples." Those human embryos were never implanted, he says. "Twins were not deliberately created, but they certainly could be."

When we speak of cloning nowadays, however, we're referring not to embryo splitting, but to a process called nuclear transfer. "The importance is that with nuclear transfer, you can copy an existing individual, and that's why there's controversy," says Griffin.

In nuclear transfer, DNA from an unfertilized egg is removed and replaced with DNA from an adult body cell -- a skin cell, for example. When the process works, the manipulated cell -- coaxed by the newly-implanted genetic material -- begins to divide and eventually becomes a genetic replica of the adult-cell donor. The process produces a new individual whose identical twin is not a minute or two older, but already grown up.

Now, researchers in South Korea and the University of Michigan have cloned a human embryo. This is not cloning to make a genetically matched baby, but cloning for research purposes -- also called therapeutic cloning or research cloning.

This new development means that therapeutic cloning -- the ability to create human clones for research purposes -- is no longer a theory, but a reality. And it's sure to reignite the controversy of whether to ban all cloning or to allow some cloning for therapeutic purposes.

Therapeutic cloning is not new. Scientists have used the technology to cure a variety of diseases in mice. Scientists have also studied the potential uses of human stem cells culled from embryos leftover in fertility clinics.

Embryo Successfully Cloned

Previous attempts to clone human embryos to obtain stem cells genetically identical to the patient are believed to have failed despite reports to the contrary -- until now.

In this new study, researchers collected 242 eggs donated by 16 South Korean volunteers. Women also donated some cells from their ovary.

The scientists then used a technique called somatic nuclear transfer to remove the genetic material -- which contains the nucleus of each egg -- and replace it with the nucleus from the donor's ovarian cell.

Then, using chemicals to trigger cell division, the researchers were able to create 30 blastocysts -- early-stage embryos that contain about 100 cells -- that were a genetic copy of the donor cells.

Next, the researchers harvested a single colony of stem cells that have the potential to grow into any tissue in the body. Because they are the genetic match to the donor, they aren't likely to be rejected by the patient's immune system.

"Our approach opens the door for the use of these specially developed cells in transplantation medicine," says Woo Suk Hwang, a scientist who led the research in South Korea.

Feasibility Questioned

But some researchers doubt that this technique for human cloning could ever be used for widespread treatment of disease.

"The great vision of this field is to create personalized stem cells for individual patients," says Griffin. "You'd take the cell from the patient and create the cell type you want -- say pancreatic islet cells for diabetics -- by transferring it to an egg, creating an embryo, and growing them."

"If there were enough women to donate enough eggs, and enough [funding], I'm certain it could be done," says Steven Stice, PhD, professor and GRE Eminent Scholar at the University of Georgia in Athens. "But we collect hundreds of eggs a day from cattle to do our cloning. You could never expect to do that in humans. Technically, it's not feasible."

"In the U.K., 120,000 people suffer from Parkinson's disease. Where are you going to get 120,000 human eggs? The reality is that there simply are not enough eggs ... available to make therapeutic cloning a practical, routine therapy," says Griffin.

And offering women money would still not yield the necessary numbers. The egg-harvesting process is just too uncomfortable. "Egg donation is akin to bone marrow transplantation as far as how unpleasant the process is for the donor," says Griffin.

And then there's money. "You'd have to produce an individual cell line for each person to avoid the immune response," says Stice. "The cost would be horrendous. It will be very difficult to get to an application [of the technology] that won't cost hundreds of thousands of dollars [each time]."

In the end, both experts agree that therapeutic cloning is really unnecessary, given the existing supply of viable embryos left over from in vitro fertilization. "They would be discarded," says Stice. "They're donated with consent, and would never have gone on to form an individual. There are great opportunities with existing cell lines to get to the point of treating disease. We don't have to go to [cloning]."

So why continue? Because of the wealth of information it can provide, says Griffin.

Cloning Doesn't Create a Twin

But there's another angle to cloning.

For some, the technology is seen not as a source for stem cells to cure disease, but as a last, best hope for biological offspring, or, mistakenly and tragically, as a means of "bringing back" a lost spouse, child, or other loved one.

First of all, says Griffin, "only about 1 to 2% of cloned animals make it to live birth." And you can't even extrapolate that number to humans, because cows and sheep get pregnant much more easily than do women. What's more, many animal clones die late in pregnancy, or early in life, he says.

Sure, there are healthy animal clones that appear to be normal. "But the tests of normality in animals are not particularly rigorous. From a safety point of view alone, no one should be attempting to clone a child," says Griffin.

Even if technology advances to the point where human reproductive cloning, as it's called, were a viable option -- and as you've seen, we're not even close -- anyone suggesting that cloning can duplicate an existing human being is just plain wrong, says Stice.

Identical twins are most certainly two different people -- they even have different fingerprints despite sharing 100% of their DNA. In the same way, your clone would be a unique individual.

In fact, says Stice, your clone would be "even less [like you] than your twin. Most twins are raised in similar environments, whereas a clone of an adult will most likely have different experiences and different environmental factors affecting them [as they grow]."

No matter how far science takes us, one thing is certain, people are simply not replaceable.