What Is a Tracheostomy?

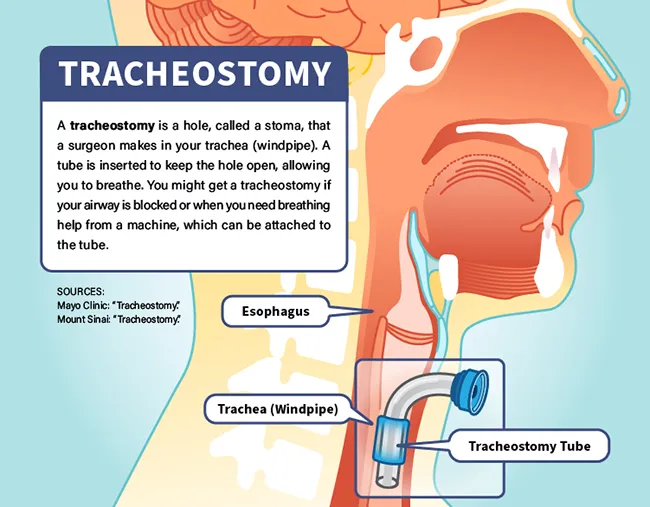

A tracheostomy is a hole in your trachea, or windpipe, that a doctor makes to help you breathe. The doctor usually puts a tracheostomy tube, sometimes called a trach (pronounced “trake”) tube, through the hole and into your windpipe. While it's in place, you breathe through the tube, rather than your nose and mouth.

Tracheotomy (without the “s”) refers to the cut the surgeon makes into your windpipe, and a tracheostomy is the opening itself. But some people use both terms to mean the same thing.

Is a tracheostomy permanent?

A tracheostomy can be temporary or permanent. Often, it's a temporary solution that helps you breathe more easily while a medical issue -- such as swelling in your airway -- clears up. Sometimes, it's in place because a medical problem is making it hard for you to breathe on your own for an extended time. In that case, the tracheostomy tube is connected to a breathing machine, called a ventilator, and will be needed as long as you need the machine.

In temporary situations, the doctor will remove the tube and close the hole once you can breathe on your own. But if there’s serious damage to your windpipe, paralysis of your vocal cords, or a critical situation such as a coma, that might not be possible.

Reasons for Tracheostomy

The main reason you would need a tracheostomy is that you can’t get enough air into your lungs. This could be because something in your upper airway is blocking it or an illness is making it hard for you to breathe. A tracheostomy also can allow doctors to clear excess mucus from your airways if you aren't able to cough it up on your own.

You could need a tracheostomy because of:

- A tumor

- Seizing vocal cords

- A spasm of your voice box (larynx)

- Injury to your windpipe or airway

- Swelling of your tongue, mouth, or airway

- Food or something else stuck in your airway

- Severe sleep apnea

- Airway b urns

- Infections

- Surgery on your face

- Larynx removal (laryngectomy)

When a serious illness keeps you from breathing well enough, treatment usually starts with a tube that goes down into the airway through your nose or mouth (intubation). The tube is connected to a breathing machine. But this kind of tube can be uncomfortable, requiring heavy sedation, and may lead to injury, ulcers, and infection if it’s left in too long. So if you’re going to need help breathing for more than a week or two, your doctor may suggest a tracheostomy. This can happen with:

- Pneumonia

- A massive heart attack

- Stroke

- Damage to the chest wall

- Chronic l ung disease

- A spinal cord injury

- Coma

- A severe allergic reaction

- Problems with the muscle below your lungs that helps you breathe (diaphragm)

- Paralysis or other conditions that make it hard to clear your airways

Tracheostomy in children

Like adults, children sometimes need a tracheotomy to breathe. The reasons are the same: blocked airways, illnesses that get in the way or breathing, or conditions that make it hard for the child to cough up mucus.

Conditions that might lead to tracheostomy in a child include:

- Syndromes a child is born with that limit airflow through the nose, mouth or throat. These include Treacher Collins syndrome and Pierre Robin syndrome.

- Nervous system problems such as cerebral palsy

- Chronic lung disease

- Tumors

- Infections

- Injuries

- Premature birth

Emergency tracheotomy

Most times, your doctor plans a tracheotomy and does the surgery in a hospital. But sometimes you need an emergency tracheotomy. This might be done outside the hospital, such as at the scene of an accident. It's most often done when the airway is blocked and emergency medical workers can't place a breathing tube through the nose or mouth. These procedures can be lifesaving, but are difficult to do and have a higher risk of complications than planned tracheotomies.

What to Expect Before a Tracheostomy Procedure

Your doctor will look at your overall health history and do a physical exam, before making a final recommendation for a tracheostomy. Before you agree to the procedure, for yourself or a loved one, you and the doctor should have a discussion about how it could help and what the risks could be.

Once the decision is made, you should meet with a team that includes a surgeon and anesthesiologist (a doctor who will make sure you aren't in pain during the surgery) to discuss the step-by-step plan.

You will get instructions on when to stop eating and drinking before the procedure and whether it's OK to take your regular medications. You might also get some additional instructions, such as not to shave your own neck that day.

Your health care team will also talk to you about what to expect once the tracheostomy is in place. (You'll get more detailed training afterwards, before you leave the hospital).

If you are not already hospitalized before your tracheotomy, you should prepare for a hospital stay that might last several days. So bring some comfortable pajamas, your toothbrush and other personal care items, and whatever you like for entertainment. Also bring some communication supplies, such as a pen and paper, a smartphone, or a computer, since you won't be able to talk immediately after the procedure.

Tracheostomy Procedure

There are two ways to do a planned operation, either as an operating room surgery or a less involved procedure that can sometimes be performed at your bedside.

Surgical tracheotomy

This is the only option for some patients, including infants. To do it:

- A nurse cleans your chest and neck with a germ-killing antiseptic.

- An anesthesiologist gives you general anesthesia , medicine to make you sleep and block pain, or makes you comfortable with numbing medication.

- The surgeon cuts into the skin on the lower half of your neck between your larynx and the top of your chest. They part the muscle and may need to move or cut the thyroid gland to get to your windpipe.

- The surgeon cuts a hole in your windpipe and puts in the tube. Stitches, surgical tape, or a strap will hold it in place.

Minimally invasive tracheotomy

A less invasive version of the operation, called a percutaneous tracheostomy, is often performed in intensive care units of hospitals. Doctors might not do it in very obese patients or people with bleeding disorders, nearby tumors, or some other injuries or disorders that increase risks. To do it:

- The team makes sure you won't feel pain (though if you are getting this procedure, you often are sedated already because you are breathing through a tube down your throat).

- The doctor threads a fiberoptic tube with a camera through your mouth to see inside your throat.

- They make a hole in your windpipe with a needle, and then expand it to the right size for the tube.

If it’s an emergency, like when you suddenly can’t breathe at all, you may be awake during the procedure. A doctor or other member of the medical team may do the surgery after injecting drugs to numb your neck.

In some emergencies, you might get a somewhat different procedure called a cricothyrotomy, which involves making a quick cut in the neck, right below the Adam's apple, and placing a tube in the hole. This is used by emergency medical teams only as a last resort when there's no other way to get air to your lungs. Once you are stable and at a hospital, a tracheostomy can replace the temporary hole.

Tracheostomy Aftercare

Expect to stay in the hospital for at least a few days after a tracheotomy. Your medical team will help you manage:

- Your trach tube. You’ll need to know how to clean it and change the inner lining to avoid problems such as irritation and infection. You may also learn to use a special machine that sucks up secretions from your windpipe or throat.

- Speech. You probably won’t be able to speak the way you usually would after your tracheotomy. You might not be able to talk at all. A speech therapist or other health care worker may give you devices or techniques to help you communicate and, as soon as possible, to talk.

- Food. As your tracheostomy heals, it will be very hard to swallow. You’ll probably get your nutrients by IV or through a feeding tube that goes into your stomach. After you are healed, a speech therapist might help you gain the strength and skills to swallow more easily so you can eat on your own again.

- Lung irritation. The air that gets to your lungs may be drier because it won’t pass through your moist nose or mouth. That can irritate the tissue inside and cause extra mucus and coughing. Nurses can teach you how to use saline solution, humidifiers, and other methods to help lessen the irritation and loosen the mucus so it’s easier to cough up.

Tracheostomy Risks

A tracheotomy is a fairly common procedure, and it’s especially safe if it’s done in a hospital. But there can be complications. Risks during or soon after a tracheotomy include:

- Bleeding

- Damage to the trachea

- Damage to the thyroid gland

- Damage to nerves that move your vocal cords

- Damage to your esophagus, or swallowing tube, which sits behind your trachea

- Air trapped in nearby tissues

- A collapsed lung

- Problems with the trach tube

- Blood that collects in your neck and presses on your trachea

Tracheostomy Complications

Complications that can happen later include:

- Infection around the tracheostomy or in your airways

- Windpipe damage or scarring

- A hole (fistula) between your esophagus and trachea

- Pneumonia

- Irritation, which can lead to an increase in mucus

- Blockage of the tube

- The tube moving out of place

Your doctor will tell you what signs to watch for if your tracheostomy develops problems after you leave the hospital. These might include:

- Bleeding from the hole

- Trouble breathing through the tube

- Pain or new discomfort

- Redness or swelling around the opening

- Movement of your tracheostomy tube

- An irregular heartbeat

- Fever

- Draining pus

- Thick mucous plugging the hole

- Crust around the hole

Call your doctor if any of those things happen.

You are more likely to have tracheostomy complications if you are a child, or if you:

- Smoke

- Have alcohol use disorder

- Have diabetes

- Have a weak immune system

- Have chronic diseases

- Have respiratory infections

- Take steroids or cortisone

Tracheostomy Tube Care

You and your caregivers can reduce the risks of complications by keeping your tube clean and well maintained.

Your healthcare team will teach you what to do. While you are still in the hospital, you'll learn to:

- Suction your tube. This clears airway secretions so it’s easier to breathe.

- Clean the suctioning device.This helps prevent infection.

- Replace the inner lining of your tube, called the inner cannula. This usually needs to be done twice a day. (Only a doctor or nurse should remove the outer tube, called the outer cannula).

- Clean the skin around your tracheostomy. This prevents irritation.

Your nurse will tell you how often you need to do these things.

If you need a tracheostomy for a while, your doctor will change your entire tube from time to time.

If you ever have trouble breathing, you should remove your inner cannula right away, since it might be blocked. If that doesn't work, call 911 or get to an emergency room right away.

You should also call 911 or get to an emergency room right away if your outer tube ever comes all the way out accidentally.

Tracheostomy Results

Your doctor will help you decide when and if it's appropriate to remove your tracheostomy tube. Before the removal, you might test your breathing by putting a cap over the tube for a day. If everything seems OK, your doctor will remove the tube.

If the tube has been in place for a short time, you won't need surgery and the opening will heal on its own, without stitches. After 16 weeks or so, you might need surgery to close the opening. You may have a small scar.

If you have a permanent tracheostomy, it may narrow over time. You may need to have more surgery to widen it.

Takeaways

A tracheostomy is usually safe. It can help you breathe for a short time, or can be an important long term solution for people who need breathing machines or have other lasting breathing issues. With proper care, you can avoid many of the complications that might come with this lifesaving measure.

Tracheostomy FAQs

How long can someone stay on a tracheostomy?

Having a tracheostomydoes not shortenyour life expectancy. Many people live a long time with a tracheostomy. But there's a lot of variation, depending on why you needed help with breathing in the first place and your overall health, age, and other factors. One study, in children with tracheostomies for a variety of conditions, found that 85% were alive after one year and 68% were alive after five years. Most, but not all, the children needed to keep the tracheostomy tubes for the whole period. Another study of older adults who left a hospital with a tracheostomy found that about 70% were alive a year later, whether or not their trach tube was attached to a breathing machine when they left the hospital. Some also had their tubes removed during the study period.

Can a person still talk with a tracheostomy?

Talking with a tracheostomy is harder, but generally possible. You can work with a speech and language therapist to learn how. One method is to simply cover your trach tube with a finger while you talk. Another method is to attach a speaking valve to the tube. Even people using ventilators can get special speaking valves. Your voice may be quieter and sound different from before. Therapists also can help you find different communication methods, such as writing, texting, pointing to pictures, or using computers and other devices.