By Bassel H. Mahmoud, MD, PhD, as told to Susan Bernstein

Vitiligo is mainly an autoimmune disease of the skin that targets pigment-producing cells called melanocytes. This results in patches of depigmentation in the form of chalky white areas on the skin that can range from very small to very large, even covering most of the skin surface.

Vitiligo affects anywhere from 0.5% to 2% of the population, both adults and children, and affects people of all ethnic groups and all skin types. Vitiligo, although most of the time considered a cosmetic problem, can have a devastating psychological effect on patients and can affect their quality of life.

Treatments for vitiligo include topical and systemic immunosuppressant medications. The one that may be best for you depends on how extensive and active your disease is. There is also phototherapy, which uses ultraviolet light and laser. Other options include surgical treatment.

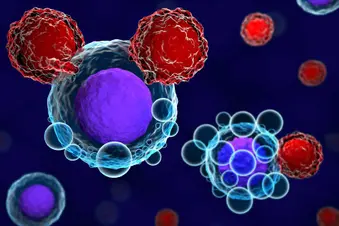

Immune T cells Attack Pigment Cells

Recent research studies have looked at the pathogenesis of vitiligo, which simply means the chain of events leading to this disease. These studies showed that vitiligo is an interferon-gamma driven disease leading to recruitment of CD8-positive T cells. These are cytotoxic T cells that engage with the melanocytes, or cells producing pigment in the skin, and kill them. Now that we have a better idea of how vitiligo occurs, we can develop better treatments to address this process. These newer treatments target and block these chains of events.

Recently developed drugs for vitiligo that have shown promising results are Janus

kinase (JAK) inhibitors. Examples include ruxolitinib and tofacitinib. Both are immune-suppressing medications that disrupt the cytokine signaling in the interferon-gamma pathway. Some of these new medicines can be used at topical creams or taken by mouth. It does take a few months to start seeing repigmentation of the vitiligo skin.

Many conventional treatments are still used and can be effective for vitiligo, such as oral and topical corticosteroids, which can have side effects if taken for a longer period of time, even topical steroids. The main side effect of topical steroids is skin atrophy, thinning of the skin. Calcineurin inhibitors, such as tacrolimus, are nonsteroidal alternative topical treatments, and they do not have the risk of skin thinning.

Light and Laser Treatments

Phototherapy is also a common, conventional treatment for vitiligo. The most used is narrow-band ultraviolet B light. It’s effective and relatively safe when used under supervision of a board-certified dermatologist. Another type of phototherapy is called PUVA, which is still used in some countries, but studies show that if it’s used for too long, it can cause skin cancer.

Previously, phototherapy treatments were done only at the dermatologist’s office two to three times a week. While it only takes a few seconds to a few minutes to get the treatment, you would still have to leave your work or school to come to your doctor’s office. Now, there are home phototherapy devices available, including many that are covered by insurance with a dermatologist’s prescription.

There is also a laser treatment for vitiligo called excimer laser. You must go to your doctor’s office for this treatment. A machine is used to target the vitiligo areas of the skin with an excimer laser. This treatment is in the ultraviolet range, but it’s a laser, not light. It’s stronger and can have a good effect on the areas that do not respond to treatment with UV light. You need to get the treatment two to three times a week.

New Cell and Tissue Transplant Surgeries

Cell transplant surgery is an option for recalcitrant vitiligo, which means when your vitiligo patches fail to respond to other conventional medications or light therapies. There are very few places in the U.S. that offer this surgery; one of them is at our department of dermatology at the University of Massachusetts. In vitiligo, there is a loss of the melanocytes in your skin, but the hair follicles in this area may have it and act as a reservoir of melanocytes. But if the hair also becomes white, then the reservoir of melanocytes is lost, and this vitiligo area will not respond to conventional therapy, and this is when a cell transplant procedure would yield the best outcome.

One type of surgical treatment is tissue transplant, such as punch grafting from normal skin and applying it to the vitiligo area. But the surface area to treat with this type of transplant is very limited. Also, the outcome is not optimum as it can cause a "cobblestone" look, which may be cosmetically unacceptable.

The other type of surgical option, which is the one I perform, is a cell transplant technique. We take a small amount of normal skin from a donor area, usually a hidden area on the body such as the upper thigh or buttock. Then, we extract the melanocytes from it and suspend them in a solution. While doing this step, we use a laser to resurface the vitiligo areas. Then, when the cells are ready, we apply them to the vitiligo patches and cover them with a bandage. This technique only requires a small area of skin to be taken from the donor site to cover a much larger area of vitiligo, which is a major advantage. The outcome leads to homogenous repigmentation without the cobblestone effect. The procedure is all done under local anesthesia as an outpatient procedure. The complications are minimal with excellent outcomes.

Talk About Your Options

When a patient with vitiligo comes into our office, they are counseled regarding the nature of their condition, different treatment options, techniques, and complications in detail. Then we come up with the best treatment plan for you. There are also many resources to help you understand vitiligo and treatment options that can be found on the American Academy of Dermatology’s website, so please visit www.aad.org for more information on skin, hair, and nail health, and www.umassmed.edu/vitiligo/ for our Vitiligo Clinic and Research Center at UMass.

Show Sources

Photo Credit: Meletios Verras / Getty Images

SOURCE:

Bassel H. Mahmoud, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology, University of Massachusetts Medical School; member, UMass Vitiligo Clinic and Research Center.