Coronavirus in Context: Challenges of Parenting During the Pandemic

Hide Video Transcript

Video Transcript

[MUSIC PLAYING]

So, ah, they're not having the social interaction. They're not going to proms. They're not having the sports. They're not having the interactions with extracurriculars or the educational patterns that they typically have.

They're doing this Zoom learning from home and all of this against a backdrop of their parents facing financial crisis because so many of their jobs, ah, are either lost or in jeopardy. And only roughly a third of parents are able to work from home. So those that can't go to their jobs have lost those jobs. So they're really worrying about what-- what they're going to do to pay their bills and those sort of things.

And all of this is happening while we're having, ah, protesters in the street and all of this, ah, activity surrounding the systemic racism that our society is being awakened to at this point. So all of this is hitting all at the same time and creating a lot of pressure on families and children in particular.

They're-- they're low maintenance. And hours can just build into hours across the week. And you realize that, ah, children have now spent 20 or 30 hours playing a video game or watching television.

And I-- I've said to parents, you know, you're not going to be the only voice in your children's ear. So you need to make sure that you're the best voice in your children ear-- children's ears, that you're the most frequent voice in your children's ear.

You don't want to abdicate your role as a parent in shaping their values, shaping their beliefs, and letting them learn some of the critical values that they need to be picking up at this time from sources that you really haven't vetted or that you really don't agree with.

So it's-- and I realize it's difficult. Parents have not been trained as educators. They're not trained as teachers. So here they are trying to do their job, and they're trying to be teachers at the same time in addition to running the household, multiple kids in-- in the house. And it's very easy to default to these electronic babysitters. And so we just have to be mindful of it and do the best that they can. And it's the hardest job in the world right now.

And one of the things that we've learned is that kids, ah, really don't know how to talk to their parents in a substantive way. It's all mechanical-- you know, how you doing? Fine. What did you do today? This or that, but not really to broach meaningful subjects. And so parents have to be the ones that open that.

And I always tell parents talk to your children about things that don't matter. And they say, why do you say don't matter? And I say it's because it's perfect practice for being able to talk to them about things that do matter when that comes up. You-- you can't just go from 0 to 60 in the blink of an eye. You've got to talk to them about casual things and--

If you can share some quality time with them playing the game, and during that time, you're talking with them, ah, that's a time where they don't feel conspicuous. And you can be actually saying so how are things going for you? In our survey, for example, we learned that 68% of the children express that they're experiencing loneliness right now. And that's because, of course, they're not spending time with their friends during quarantine.

Well, it-- it's OK for you to be a friend to them, as well as their parent, during this time. Your role is parent, but you can also hang with them some, learn some things about their world. This doesn't have to be all pressure. It can be a time that you can really bond and do some things with your child that you haven't had time to do before.

And so while all of this is going on, I think we need to be very committed as parents and-- and parent on purpose as opposed to being reactive, which maybe we can get away with more when children have different outlets in their life than they do during quarantine.

And this is a time, for example, that we need to, you know, share these interactions. We need to purposely create family dynamics. And the stranger it feels, the more corny it feels to have a-- a family meeting in the living room or around the kitchen table--

If you have a meal together, if you sit down and talk about what you did today, if you can find something that they can tell a story about, then those interactions take the place of being on a video game, takes a place of them sitting in their room just thinking about who knows what? Ah, and--

And your answers need to use the terms, the language, the level of understanding that they're asking. You don't want them to meet you where you are. You want to meet them where they are in their understanding. So if they're saying, you know, mommy, daddy, is-- is everybody getting sick? Is-- is this just something that like a bad cold or the flu? Ah, is-- is that what's going on? Then you answer at that level and explain.

As children get older, and they're talking about, look, this is a-- this is a novel virus that's never happened before, and we don't have a vaccine for it, OK, now they're more sophisticated in their understanding.

So you can discuss it at that level. But right now, there are so many conflicting reports and resources. And it's changing every day because this is a novel virus that we need to really limit where they're getting their information. And be sure that it's a trusted and nonpoliticized source.

And when we are in a prolonged quarantine like this, and we have stress, we have anxiety, we have depression, then we know that-- that this impacts physical illness. We know that it cause-- has caused people to put off screening for different diseases.

We know that it's caused them to put off treatment for existing diseases that has allowed those things to advance. So there is no question that the-- the-- the mental illness aspects of this have had a profound effect on physical illness.

That's a concern of mine. And I'm also very concerned about the anxiety, depression, loneliness, PTSD, many of the things that people are experiencing because of the fear they have, ah, of this virus, the loneliness they're experiencing through isolation.

All of these things are obtaining in various mental illnesses that are oftentimes going untreated because the people either don't have resources, or they're afraid to go seek that, ah, in a doctor's office right now. So I'm very concerned with the mental-- ah, mental health aspects of this. And I think that could be as profound an impact long term as the virus itself.

But exercise and being outside is a great outlet. That's what I do. I've been a jock all of my life, never a good athlete, but a persistent one. So I've always, ah, found an outlet in exercise and getting outside.

And I think it is extremely important to give your feelings a voice. Talk about your feelings so you don't think you're the only one feeling that way and that you are bottling this stuff up inside. Give your feelings a voice. Talk about it. Let it out. I think that's so very, very important. And for me, exercise and that sort of release has been huge.

Ah, sadness, of course, argumentativeness, these things that vary from baseline will tell you that your child is experiencing emotional upheaval. And when that's true, that's the time that you want to sit down with your child and say, tell me what you're feeling inside. Let's talk about this. How can I help? Let's-- let's give this a voice and-- and talk about it. And hopefully, you'll be surprised at how forthcoming they are because they're looking for an outlet.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

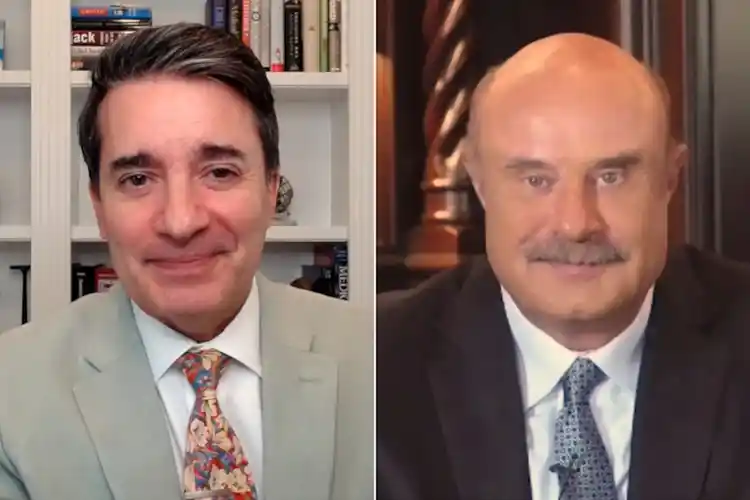

JOHN WHYTE

Hi, everyone. You're watching Coronavirus in Context. I'm Dr. John Whyte, chief medical officer at WebMD. Is there a crisis in parenting? My next guest, Dr. Phil McGraw, best-selling author, host of the Dr. Phil Show, says there is. Dr. Phil, thanks for joining me. PHIL MCGRAW

So glad to be here. JOHN WHYTE

I want to talk about this interesting editorial you wrote in The Hill where you talk about a multidimensional precipice that we're get on. What do you mean by that? PHIL MCGRAW

Well, I mean that we've kind of got a perfect storm of psychosocial influences that, ah, both parents and children are facing right now. If you think about it, ah, there's been so much disruption, ah, particularly for children. Ah, their schedules have been disrupted. They're not in school, which means they're not experiencing the social interactions that they normally have. They're not having the schedules that they normally have. So, ah, they're not having the social interaction. They're not going to proms. They're not having the sports. They're not having the interactions with extracurriculars or the educational patterns that they typically have.

They're doing this Zoom learning from home and all of this against a backdrop of their parents facing financial crisis because so many of their jobs, ah, are either lost or in jeopardy. And only roughly a third of parents are able to work from home. So those that can't go to their jobs have lost those jobs. So they're really worrying about what-- what they're going to do to pay their bills and those sort of things.

And all of this is happening while we're having, ah, protesters in the street and all of this, ah, activity surrounding the systemic racism that our society is being awakened to at this point. So all of this is hitting all at the same time and creating a lot of pressure on families and children in particular.

JOHN WHYTE

You talked about targeted parenting. You know, you just mentioned the stress of parenting now. And you also reference the dangers of electronic babysitting. What do you say, though, to the parents who are-- you know what-- they're trying to manage as many things that they can? And sometimes, the pad, the games, gives them some respite, ah, from, you know, all that's going on in the home to-- to get other things done. How do you manage it all, Dr. Phil? PHIL MCGRAW

It's very, very difficult. And video games, television, to a degree, of course, are acceptable. Ah, but it can also be-- be sweet poison because it's very easy because of the convenience. You know, the kids can go off in the corner or go off in their room. And they're quiet. They're-- they're low maintenance. And hours can just build into hours across the week. And you realize that, ah, children have now spent 20 or 30 hours playing a video game or watching television.

And I-- I've said to parents, you know, you're not going to be the only voice in your children's ear. So you need to make sure that you're the best voice in your children ear-- children's ears, that you're the most frequent voice in your children's ear.

You don't want to abdicate your role as a parent in shaping their values, shaping their beliefs, and letting them learn some of the critical values that they need to be picking up at this time from sources that you really haven't vetted or that you really don't agree with.

So it's-- and I realize it's difficult. Parents have not been trained as educators. They're not trained as teachers. So here they are trying to do their job, and they're trying to be teachers at the same time in addition to running the household, multiple kids in-- in the house. And it's very easy to default to these electronic babysitters. And so we just have to be mindful of it and do the best that they can. And it's the hardest job in the world right now.

JOHN WHYTE

So how do we put limits on? Because if we tell parents, you know, it's not all or none, right? Ah, we're trying to find the balance. How do we know what that right balance is, Dr. Phil? Is-- is it a matter of an issue of time? Is it an issue on circumstance? What's your guidance on that? PHIL MCGRAW

Well, you know, I think it is a matter of first-- one of the things that we've really learned as we've been talking to parents through this-- and, ah, Dr. John Chirban from Harvard Medical School, a colleague of mine, he and I have conducted a survey. We're writing the results up on it now. And one of the things that we've learned is that kids, ah, really don't know how to talk to their parents in a substantive way. It's all mechanical-- you know, how you doing? Fine. What did you do today? This or that, but not really to broach meaningful subjects. And so parents have to be the ones that open that.

And I always tell parents talk to your children about things that don't matter. And they say, why do you say don't matter? And I say it's because it's perfect practice for being able to talk to them about things that do matter when that comes up. You-- you can't just go from 0 to 60 in the blink of an eye. You've got to talk to them about casual things and--

JOHN WHYTE

Like give us an example. Like-- like what would-- PHIL MCGRAW

Well-- JOHN WHYTE

--we talk about them now? PHIL MCGRAW

For example, it's important to talk to them about music in their world, the video games that they are playing, the the-- things that they're entertaining themselves with. Instead of judging those things, say tell me about your game. Show me how this works. The music you're listening to, why are you interested in that? Instead of judging it, learn about it. Listen to it. They'll become enthused about it because it's their passion. If you can share some quality time with them playing the game, and during that time, you're talking with them, ah, that's a time where they don't feel conspicuous. And you can be actually saying so how are things going for you? In our survey, for example, we learned that 68% of the children express that they're experiencing loneliness right now. And that's because, of course, they're not spending time with their friends during quarantine.

Well, it-- it's OK for you to be a friend to them, as well as their parent, during this time. Your role is parent, but you can also hang with them some, learn some things about their world. This doesn't have to be all pressure. It can be a time that you can really bond and do some things with your child that you haven't had time to do before.

JOHN WHYTE

You mentioned targeted parenting. And-- and these are some of the elements of that targeting. But how is it different than maybe what they were doing pre-COVID? Do we have to do different things as parents? Or should we be doing different things as parents in the middle of a pandemic? PHIL MCGRAW

I-- I think we do have to do some things different that-- and when I say targeted, the challenges are different now. Our children are living with an invisible enemy. And they're living as I said with this perfect storm. And our job as parents is to prepare the child for the next level of life. And so while all of this is going on, I think we need to be very committed as parents and-- and parent on purpose as opposed to being reactive, which maybe we can get away with more when children have different outlets in their life than they do during quarantine.

And this is a time, for example, that we need to, you know, share these interactions. We need to purposely create family dynamics. And the stranger it feels, the more corny it feels to have a-- a family meeting in the living room or around the kitchen table--

JOHN WHYTE

Does feel corny. I'm going to be honest. It feels corny, but go on. PHIL MCGRAW

I'm telling you the-- the-- the more corny it feels, the more you need to do it. And they'll roll their eyes. And they'll say, oh, come on, Mom. Come on, Dad. But I'll tell you what. It still has an impact. If you have a meal together, if you sit down and talk about what you did today, if you can find something that they can tell a story about, then those interactions take the place of being on a video game, takes a place of them sitting in their room just thinking about who knows what? Ah, and--

JOHN WHYTE

Yeah. PHIL MCGRAW

--it's very important that you limit their exposure to all of this that's going on. Find a trusted source. Check in in the morning. Check in in the evening. Keep them away from that during the day. And when they do watch it, watch it with them so you can answer their questions. JOHN WHYTE

Is it different for kids that are younger, say, you know, first grade through sixth grade, elementary school, than it is for high school students? Do we do different targeting? PHIL MCGRAW

You do. We always hear this term age appropriate, but nobody ever really defines that. And let me talk about how I'd like to define that. I define that by saying how important it is to listen. You-- you find out what's age appropriate by listening to what your child understands. If you're talking about the pandemic, listen to what they understand. What questions do they ask? And your answers need to use the terms, the language, the level of understanding that they're asking. You don't want them to meet you where you are. You want to meet them where they are in their understanding. So if they're saying, you know, mommy, daddy, is-- is everybody getting sick? Is-- is this just something that like a bad cold or the flu? Ah, is-- is that what's going on? Then you answer at that level and explain.

As children get older, and they're talking about, look, this is a-- this is a novel virus that's never happened before, and we don't have a vaccine for it, OK, now they're more sophisticated in their understanding.

So you can discuss it at that level. But right now, there are so many conflicting reports and resources. And it's changing every day because this is a novel virus that we need to really limit where they're getting their information. And be sure that it's a trusted and nonpoliticized source.

JOHN WHYTE

We've been talking to, ah, Kenneth Cole, Deepak Chopra, Arianna Huffington, who have all been talking about this mental health pandemic that we're having. So here, we have an infectious disease pandemic with COVID. How concerned are you about mental health in adults? In children? All the way around? PHIL MCGRAW

Well, I'm very concerned about it and a-- as are others. If you look in the-- The Journal of Pediatrics and JAMA, you see that any time there is prolonged stress, ah, pressure, and anxiety, then it can convert to physical illness. It exacerbates existing illness. It can bring on illnesses. And when we are in a prolonged quarantine like this, and we have stress, we have anxiety, we have depression, then we know that-- that this impacts physical illness. We know that it cause-- has caused people to put off screening for different diseases.

We know that it's caused them to put off treatment for existing diseases that has allowed those things to advance. So there is no question that the-- the-- the mental illness aspects of this have had a profound effect on physical illness.

That's a concern of mine. And I'm also very concerned about the anxiety, depression, loneliness, PTSD, many of the things that people are experiencing because of the fear they have, ah, of this virus, the loneliness they're experiencing through isolation.

All of these things are obtaining in various mental illnesses that are oftentimes going untreated because the people either don't have resources, or they're afraid to go seek that, ah, in a doctor's office right now. So I'm very concerned with the mental-- ah, mental health aspects of this. And I think that could be as profound an impact long term as the virus itself.

JOHN WHYTE

Tell our listeners how Dr. Phil deals with stress. What-- what can we learn from you? What-- what are your tips and tools? PHIL MCGRAW

Well, you know, for me a big outlet is exercise, you know, being outside which, of course, is one of the safer environments we can be in during this time if we maintain social distancing, we wear our mask. And Robin and I have committed wholly to the CDC guidelines of maintaining quarantine, social distancing when we go out, wearing our mask. But exercise and being outside is a great outlet. That's what I do. I've been a jock all of my life, never a good athlete, but a persistent one. So I've always, ah, found an outlet in exercise and getting outside.

And I think it is extremely important to give your feelings a voice. Talk about your feelings so you don't think you're the only one feeling that way and that you are bottling this stuff up inside. Give your feelings a voice. Talk about it. Let it out. I think that's so very, very important. And for me, exercise and that sort of release has been huge.

JOHN WHYTE

And then for parents and caregivers, what are those red flags that we should look out for? PHIL MCGRAW

Well, there are a number of red flags. And I think that when you-- when you watch your children, you have to take a baseline. Think about where they were before the pandemic. And compare that to their behavior now. And the biggest things that jump out-- look for sleep disturbance. And that can be too much sleep or not enough sleep. But if it varies from the baseline, that's a big red flag. Irritability, ah, is a really big thing. Ah, sadness, of course, argumentativeness, these things that vary from baseline will tell you that your child is experiencing emotional upheaval. And when that's true, that's the time that you want to sit down with your child and say, tell me what you're feeling inside. Let's talk about this. How can I help? Let's-- let's give this a voice and-- and talk about it. And hopefully, you'll be surprised at how forthcoming they are because they're looking for an outlet.

JOHN WHYTE

And that's a good point to-- to recognize it and then having symptoms and seek help if you need to. I want to thank you, Dr. Phil, for taking the time today. I want to thank you for all that you've been doing for 18 years and more raising awareness on issues, giving voice to patients to-- to think through how do we exhibit and demonstrate resilience, um, and get through this pandemic. So thank you for all that you're doing. And thank you for taking the time today. PHIL MCGRAW

Well, thank you, and just know that WebMD is one of my prime, ah, resources when I'm going to look things up and learn about cutting edge information today. So we appreciate all that you guys are doing as well. JOHN WHYTE

Well, thank you. [MUSIC PLAYING]