No Joke

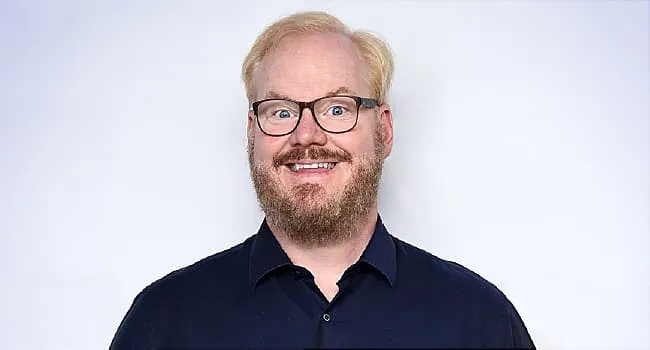

Last year, comedian Jim Gaffigan and his writer wife, Jeannie, faced a health crisis that nearly ended her life, derailed their family, and halted his career. But innovative technology -- and a little humor -- got them through.

Yes, Jim’s a famous comedian. But ignore his film work, late night appearances, and standup gigs, and the Gaffigan family is like any other loving, if slightly frantic, large clan. Jim and partner Jeannie (in marriage and material -- she’s a writer, producer, and his frequent collaborator) together juggle five young children, joke-making, and insane schedules. And they do their best not to drop any balls, least of all when it comes to their health.

So when Jeannie developed crushing headaches, frequent falls, and severe fatigue in the final months of 2016, she chalked it up to, well, life. The busy mom thought, I don’t have time for this! “I figured I had the flu,” she says.

It was her kids’ pediatrician who first raised a red flag during a routine visit. That is, if you deem “routine” a single appointment last April with all five children, two daughters and three sons (now) ranging in age from 4 to 13, in tow.

After noting her rattling cough, the doctor switched focus from the Gaffigan brood to their mother, who couldn’t hear much out of her left ear, either. An impromptu examination showed no obvious signs of inflammation, so she suggested Jeannie immediately see an ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist.

She complied. And didn’t think much of it. She certainly never imagined she’d find herself about to be wheeled into major surgery a few days later, a frightened Jim at her side.

It all happened so fast: The ENT ordered an MRI scan of Jeannie’s head, which revealed a 6-centimeter tumor the size of a tennis ball growing within the tightly contained space of her brain stem. While it eventually tested benign, its dimensions and location were particularly dangerous. Had it gone unchecked for even a short time longer, she would have had problems thinking and remembering, paralysis, and very likely death, according to her doctor, Joshua Bederson, MD, at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York.

“We did tell our two older children what was happening because we knew the household was about to be disrupted dramatically,” Jim says in a phone call from his hotel room just a few hours before he performed a comedy set in New Orleans. “So we did to them what the doctors did to us: presented the information with a positive, glass half-full approach,” even if his true level of anxiety, he admits now, was off the charts.

Tumor Humor

Both Gaffigans subdued their fears through countless prayers, an action plan that included checking into Mount Sinai’s emergency room after learning top surgeon Bederson worked there, and staying true to their shared modus operandi: being funny.

“Jeannie came out of the MRI machine with new material, saying, ‘Hey, Jim! Write this down,’” the Cinco comedy special star recalls, his tone relaxed with hindsight.

His wife, a Milwaukee native, agrees. “I asked the technicians what would happen if I screamed in there,” she says, “and they were, like, ‘Oh, that’s OK. We can’t hear you, anyway.’”

MRI machines can be cramped, coffin-like spaces that emit loud, whirring noises, causing panic in some patients who suffer from claustrophobia. Bederson ordered Jeannie to undergo an additional 7 hours of these and other imaging tests in the days before her surgery to produce what he calls “a 3-D virtual reality simulation of her brain.” This “cutting-edge, augmented reality technology” enabled him to remove the tumor with a high degree of precision “not possible even a year or two ago.”

Despite their daunting situation, the Gaffigans kept searching for the joke. “That’s the way we deal with life: with humor,” says Jeannie of herself and her husband of 14 years. “Fight or flight, we went with fight. The fight was using humor to cope with tragedy.”

Fans of Late Night with Seth Meyers sampled this in Jim’s updated act, now replete with brain tumor jokes that were co-written by the patient herself.

“It was really scary for a while,” Jim told Meyers last June, just weeks after the operation, his deadpan expression and tone giving nothing away. “There were moments when I was like, ‘Oh, my gosh. If anything happens to my wife, those five kids are going to be put up for adoption.”

Kidding aside, Jim is the first to emphasize just how gutted he’d be without his other beloved half. He’s been known to call her his “secret weapon” for helping craft such punch lines, often inspired by hilarious moments pulled from family life.

Still, it was tough to find the funny once reality set in. “Obviously, I selfishly wanted my wife to be OK because I love her. But I was also concerned about my children. It’s one thing for them to go from super mom to klutzy dad. Then there were moments when I was like, ‘Oh. No. This might be it.’ And if things went further south, the priority would be for me to be the continuity in my children’s lives. I knew I couldn’t do that and tour as a comedian and be an actor in films,” says Gaffigan, who next appears in the big screen drama Chappaquiddick in April. “When we finally got out of the woods, my obvious gratitude was about Jeannie. And also, it was, ‘OK. I could have lost this whole thing.’”

He and his wife are devout Catholics who don’t shy away from using the word “miracle” when it comes to Jeannie’s eleventh-hour diagnosis and subsequent survival. Jim says he’s been irrevocably “changed by the experience. The writing we do, there’s been a shift. The simple process about talking about it all in a humorous manner has been cathartic for me, but I think it’s cathartic for others to hear about it, too. There’s not a single person out there who hasn’t lost, or almost lost, an important person in their lives.”

Post-Op Perseverance

Choroid plexus papilloma is a rare and benign tumor that grows within the brain stem, a crucial region that controls the flow of messages between the brain and the rest of the body, as well as basic bodily functions such as swallowing, heart rate, blood pressure, consciousness, feelings of sleepiness, and even breathing.

“The brain stem is what we call high-price real estate in neurosurgery,” Bederson says. “It’s chock-full of critical structures.” Patients with Jeannie’s condition generally first get pneumonia, he explains, because they have trouble swallowing saliva and food, which gets sucked into the lungs. Other symptoms include “loss of cranial nerves, speech issues, respiratory depression, loss of balance and functionality, painful headaches, debilitating fatigue, and weakness,” all of which Jeannie had.

It’s unusual for someone Jeannie’s age to be diagnosed with this type of mass. The condition is more common in children and represents only 2% to 4% of all tumors in adults. But what made her growth so remarkable, Bederson says, was its “huge” size, a factor that immediately suggested it was likely not cancerous but still destructive.

After seeing her first scan from the ENT, “I couldn’t believe she was able to walk into my office by herself, much less care for five children,” he says. Which is why he ordered her immediate treatment.

The surgery went well. Jeannie even posted a photo on Instagram of herself kissing one of her young sons from her ICU bed, captioning it, “I’m still alive!”

Recovery, however, didn’t go quite so smoothly. The writer’s brain stem had endured so much compression from the tumor that her ability to swallow was still seriously weakened. The night following the operation, “I aspirated my saliva and developed double-lung strep pneumonia,” she says, which compelled Bederson to perform a tracheotomy to her neck to open up her airways, followed by the insertion of a feeding tube into her naval cavity. She relied upon both for months as she battled back from illness.

Once stabilized about 2 weeks post-surgery, Jeannie returned home to the Gaffigans’ Manhattan apartment to recover.

“Our youngest sons dressed up like doctors to care for her,” Jim says. “They showed so much compassion.” He chokes up a bit when describing how family members flew in from the Midwest “without hesitation” and how so many “amazing” friends from all walks of life appeared to help with the kids as she began speech and swallowing therapy and other rehabilitative work to restore her brain functionality, body strength, and balance.

Jeannie still struggles with roughly 50% hearing loss out of her left ear and is only now, many months later, graduating from a liquid diet. But “her 60% is my 110%,” Jim told the San Francisco Chronicle last September of her rebound.

He saves special (comic) praise for Bederson. “He’s the best,” Jim insists in all seriousness before musing, “I don’t how they determine who the ‘best’ brain surgeon is. Maybe there’s a competition -- you know, America’s Got Tumors or something. And why does someone have to be the best brain surgeon? Isn’t it enough that he’s a brain surgeon?”

Bederson is equally effusive about the Gaffigans, his recent patient in particular. The neurosurgeon sees her rapid improvement as nothing short of astounding. “Have you met Jeannie?” he asks, almost amused. “She’s very petite, very athletic. And such a trouper.”

High-Tech Surgery

Bederson co-directs Mount Sinai's Neurosurgery Simulation Core, one of the first academic neurosurgery simulation research centers in the world. Bederson and his colleagues use innovative technology that “creates a GPS for the brain,” allowing them to see -- and most importantly, avoid -- critical parts of the brain with 3-D computerized imaging as they remove a tumor. This virtual reality technology, now available at some of top hospitals in the U.S., first entered surgical theaters in 2015. Here’s how it works:

Layered Imaging

“Think of the movie Avatar,” Bederson says, “in which we create a virtual reality simulation of a [specific] case based on multiple information sources including MRI, CT scan, and angiogram. We co-register and segment them, meaning we color them, make them transparent, and attach different properties to each different type of tissue -- cranial nerves, blood vessels, brain stem, cerebellum, and bones. Each tissue has its own appearance and [is] overlapping and integrated [on a computer screen]. It’s like a 3-D virtual reality scenario, but based on [an individual’s specific] anatomy and pathology.”

Better Precision

“We have an instrument that knows where my [surgical] instruments are in relation to the patient’s anatomy,” he says. “We track the microscope’s movement and where the focal point of the microscope is, so the computer knows where my eyes are looking and where my eyes are focused.

“If I want to know where the brain stem is when I’m working on a tumor, normally I wouldn’t be able to see it because the tumor’s [in the way]. Now you have control over the simulation. You can see around corners.” This provides neurosurgeons like Bederson a level of precision and safety previously more difficult, if not impossible, to achieve.

Find more articles, browse back issues, and read the current issue of "WebMD Magazine."