What Is COPD?

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a long-term lung condition that makes it hard for you to breathe. COPD is a progressive disease, meaning it gradually gets worse over time.

Types of COPD

COPD is an umbrella term used when you have one or more of these conditions:

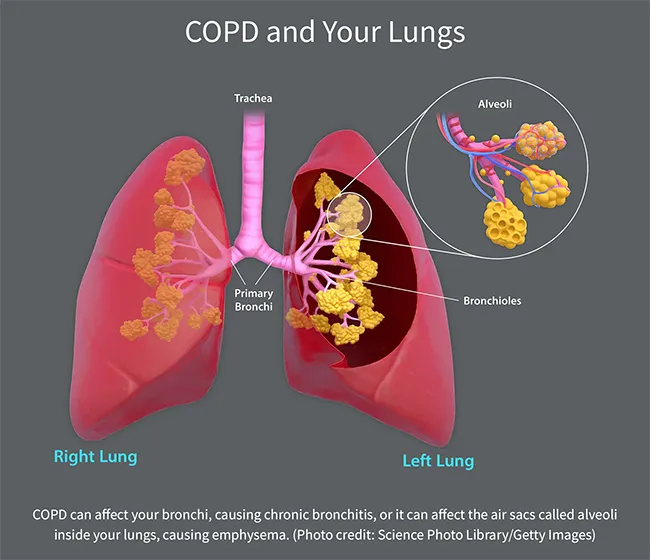

Emphysema. This results from damage to the small air sacs, called alveoli, inside your lungs. These little sacs transfer oxygen from your lungs to your bloodstream. When they get damaged, their walls break down, leaving larger air spaces in your lungs. These don't work as well to get oxygen into your blood. Also, when you breathe out, trapped air stays in your lungs, leaving less room for fresh air and making you feel short of breath.

Chronic bronchitis. If you have coughing, shortness of breath, and mucus that lingers at least 3 months for 2 years in a row, you have chronic bronchitis. This happens because of irritation of your bronchial tubes, the two large tubes that carry air from your windpipe to your lungs. Hair-like fibers called cilia line these tubes and help move mucus out. When you have chronic bronchitis, you lose your cilia. This makes it harder to get rid of mucus, which makes you cough more, which creates more mucus.

Asthma-COPD overlap syndrome. If you have asthma that doesn't respond to usual treatments along with breathing problems typical of COPD, your doctor may give you this dual diagnosis. Your doctor also might say that your asthma is "refractory" or severe. Most people with asthma do not have COPD.

COPD Causes

Long-term exposure to things that irritate your lungs is the most common cause. In the U.S., that’s cigarette, pipe, or other types of tobacco smoke. Smoking causes about 90% of COPD.

Tobacco smoke triggers irritation and swelling, narrowing your airways. It also damages cilia, so they can't clear mucus as well.

Other causes can include:

- Marijuana smoke

- Secondhand smoke

- Air pollution

- Chemical fumes

- Dust

- A rare genetic disorder called AAT (alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency) that can lead to emphysema

Risk Factors for COPD

You are more likely to develop COPD if you:

- Smoke. The risk is highest for cigarette smokers and increases with the number of years and amount you smoke, whether it's cigarettes, pipes, or cigars.

- Spend a lot of time around other smokers

- Work around certain chemicals or dust from grain, wood, or mining products. Your risk is higher if you also smoke.

- Live or work where there are high levels of outdoor or indoor air pollution -- which can come from heating oil fumes, car exhaust, industry, wildfire smoke, and other sources

- Were assigned female at birth. Studies find women who smoke are 50% more likely than male smokers to develop COPD.

- Are between ages 40 and 60

- Had a lot of respiratory infections as a child

COPD Symptoms

At first, you might not have any symptoms. But as the disease gets worse, you might notice these common signs of COPD:

- A cough that doesn't go away

- Coughing up lots of mucus

- Shortness of breath (trouble taking a deep breath and feeling like you can't get enough air)

- Worsening shortness of breath when you climb stairs, walk, do other exercise, or perform regular daily activities

- Wheezing or squeaking when you breathe

- Tightness in your chest

- Frequent colds or flu

As the disease progresses further, you may also have:

- Trouble walking as far as you once did

- Needing to sit up or prop yourself up on more pillows to sleep

- Unintentional weight loss

- Feeling winded during long conversations

- Swollen ankles, feet, or legs

- Blue fingernails

- Low energy

COPD Diagnosis

Your doctor will ask about your symptoms, your medical history, and whether you smoke or have been exposed to chemicals, dust, or smoke at work. They'll ask questions like:

- How long have you been coughing?

- What makes your shortness of breath worse?

- Do you cough up mucus?

They’ll also do a physical exam. During the exam, they will:

- Listen to your lungs and heart

- Check your blood pressure

- Check your pulse

- Examine your nose and throat

- Check your feet and ankles for swelling

They'll also order some tests.

COPD Tests

The most common test is called spirometry. You’ll breathe into a large, flexible tube that’s connected to a machine called a spirometer. It’ll measure how much air your lungs can hold and how fast you can blow air out of them.

Your doctor may order other tests to see how COPD might be affecting you and to find or rule out other lung problems, such as asthma or heart failure. These might include:

Pulse oximetry. This is a simple test to detect oxygen levels in your blood. It's usually done with a small device clipped to your finger.

Arterial blood gases (ABGs). This uses blood drawn from an artery in your wrist, arm, or groin to check how well your lungs are bringing in oxygen and taking out carbon dioxide.

Chest X-rays. These can help find signs of emphysema, other lung problems, or heart failure.

CT scan. This can create a detailed picture of your lungs. It can tell the doctor if you need surgery or if you have lung cancer.

Electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG). This test checks heart function and can rule out heart disease as a cause of shortness of breath.

Laboratory tests. These can help determine the cause of your symptoms or rule out other conditions, like the genetic disorder alpha-1-antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency.

Exercise testing. You may walk on a treadmill or ride a stationary bike for a few minutes so that your doctor can see how your heart and lungs respond.

COPD Stages

Doctors often describe the way COPD progresses in four stages, which you might hear described as GOLD grades. GOLD stands for Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. That's a group that sets widely used guidelines for COPD treatment.

These stages are based in part on how badly your airflow is blocked as measured by spirometry, the same test you get when you are diagnosed. In particular, your doctor will look for how much air you can breathe out at one time and how much air you blow out in the first second of a hard exhale.

Your doctor also will consider:

- Your symptoms and how bad they are

- How many times you've had moderate to severe flare-ups (also known as exacerbations)

- Whether you have other chronic diseases

You can expect different symptoms and challenges at each stage.

Stage 1: Mild COPD

You may have no symptoms or feel a little out of breath when you walk up stairs or do moderate exercise. Your airflow is about 80% of normal.

Stage 2: Moderate COPD

You might need to stop and catch your breath when walking on level ground. You may be coughing and wheezing. Your airflow is 50%-79% of normal.

Stage 3: Severe COPD

Your shortness of breath is getting worse and getting in the way of things you want to do every day. Your airflow is 30%-50% of normal.

Stage 4: Very Severe COPD

This is also called end-stage COPD. At this point, it's hard to catch your breath, even when you are sitting or lying down. You may have flare-ups that put you in the hospital and threaten your life. Your airflow is less than 30% of normal.

In addition to these stages, your doctor may put you in a group, labeled A,B,C, or D, based on how likely you are to have flare-ups. This is when your COPD symptoms suddenly get worse. Group A has the lowest risk and group D has the highest.

All of these factors will influence which treatments you try.

COPD Treatments

There’s no cure, so the goal of treatment is to ease your symptoms and slow the disease. Your doctor will also work with you to prevent or treat any complications and improve your overall quality of life.

One of the best things you can do to stop your COPD from getting worse is to stop smoking. Talk to your doctor about ways you can try to quit smoking, even if you've tried many times before.

Medication for COPD

Your plan may include:

- Bronchodilators. You usually inhale these medicines. They help open your airways.

- Corticosteroids. These drugs reduce airway inflammation. You could inhale them or take them as pills.

- Combination inhalers. These inhalers pair steroids with one or more bronchodilators.

- Antibiotics. Your doctor might prescribe these to fight bacterial infections.

- Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors,such as roflumilast (Daliresp). This drug stops an enzyme called PDE4. It prevents flare-ups in people whose COPD is linked to chronic bronchitis.

- Anticholinergics. These drugs relax airways and help clear mucus from the lungs. They work more slowly than bronchodilators.

- Leukotriene modifiers. These drugs interfere with natural chemicals in the body that tighten airways and increase mucus and fluid.

- Theophylline. This is a bronchodilator you can take as a pill or liquid. Because low doses haven't proven effective and high doses come with side effects, including nausea and headaches, it's usually only used when other treatments aren't working or are too expensive for you.

- Antihistamines. If you have allergy symptoms such as stuffiness, watery eyes, and sneezing, these drugs can help -- but they can also dry your airways, causing more coughing

- Antivirals.If you get a treatable viral illness, like the flu or COVID-19, your doctor can prescribe these drugs to lessen the risk of COPD complications

- Flu, pneumonia, and COVID-19 vaccines. These vaccines lower your risk for respiratory illnesses that can make your COPD worse.

COPD surgery

In severe cases of COPD, your doctor may suggest:

- Bullectomy to remove bullae, large air spaces that form when air sacs collapse

- Lung volume reduction surgery to remove diseased lung tissue

- Lung transplant to replace a diseased lung with a healthy one

Other COPD treatments

Pulmonary rehabilitation. This program includes exercise, nutrition advice, and counseling to help you stay as healthy and active as possible.

Oxygen therapy. As your COPD progresses, you may need extra oxygen while you sleep or do certain activities, or you might need it all the time. Oxygen can reduce shortness of breath, protect your organs, and help you live longer.

In-home noninvasive ventilation therapy. Some people with advanced COPD who have severe trouble breathing out carbon dioxide get a breathing device to use at home. One such device is a bilevel positive airway pressure, or BiPap, machine. You wear a mask or nasal plugs attached to the machine while it helps push air into your lungs.

If you aren't getting enough relief from standard treatments, you might ask your doctor about joining a clinical trial. That's a study in which new treatments are tested, though not everyone in the study may get the treatment. Not everyone is a good fit for a study.

Complications of COPD

COPD can cause everyday complications, such as:

Inactivity. When you move less because of shortness of breath, that can increase your risk of many other health problems, including loss of bone and muscle, which can make it even harder for you to move around.

Depression and anxiety. Trouble breathing can stop you from doing things you like. And living with a chronic illness can lead to depression and anxiety. Your doctor can help if you feel sad, helpless, or would like to see a mental health professional.

Lost work and income. You may take more sick days and retire earlier than you want because of your symptoms.

Social isolation and loneliness. Your problems with breathing and mobility may keep you away from social gatherings. Loneliness is especially high among those who use supplemental oxygen.

Confusion and memory loss. Your chronic problems breathing in enough oxygen and breathing out enough carbon dioxide can affect your thinking abilities. Smoking can make those effects worse.

COPD is also linked with increases in many other health problems, like:

Respiratory infections. COPD can raise your chances of getting colds, the flu, and pneumonia. They make it harder for you to breathe and could cause more lung damage. Infections also can trigger COPD flare-ups. Staying up to date on all vaccines can help.

Heart problems. Doctors aren’t sure why, but COPD can raise your risk of heart disease, including heart attack. Quitting smoking may lower the odds.

Lung cancer. People with COPD are more likely to get lung cancer. Quitting smoking can help.

High blood pressure in lung arteries. COPD may raise blood pressure in the arteries that bring blood to your lungs. Your doctor will call this pulmonary hypertension.

Living With COPD

Though there’s no cure, there are things you can do to stay healthy and ease your symptoms. Try taking these steps to enhance your quality of life:

- If you smoke, stop.

- Avoid smoke, fumes, dust, and air pollution as much as you can.

- Take your medications as directed.

- Get regular checkups.

- Do breathing exercises and controlled coughing, which you can learn from a pulmonary rehabilitation specialist.

- Walk or do other light exercise several times a week.

- Eat a healthy diet. Some people find that eating more fats and fewer carbohydrates helps them breathe better.

- Get plenty of fluids. Aim for six to eight 8-ounce glasses a day unless your doctor gives you other guidelines.

- Get enough sleep and rest.

- Use a humidifier when your indoor air is dry.

- Get emotional support through counseling or a support group.

- Manage your stress.

- Keep your house free of dust and mold.

- Make sure the vent over your stove works, and use it to limit your exposure to cooking fumes.

- Stay away from sick people and avoid crowds during cold and flu season.

- Be alert for signs of a flare-up, like more coughing, wheezing, and tiredness, and be ready to respond.

COPD Exacerbations

There may be times when your symptoms get worse for days or weeks. You might notice you’re coughing more with more mucus, have more trouble breathing, are struggling more to sleep, and feel worse. Your doctor will call this an acute exacerbation or a flare-up. If you don’t treat it, it could lead to lung failure.

Make sure you talk to your doctor about what to do when you notice a flare-up starting. You might need to take extra medicines or take other steps to keep symptoms under control.

Your doctor might prescribe antibiotics if you have a bacterial infection or steroids to tamp down inflammation. Or you might need oxygen treatments. In some cases, you'll need to go to the hospital. When you’re better, talk with your doctor about how to lower the risk of flare-ups. They may recommend you renew efforts to quit smoking and avoid triggers like exposure to secondhand smoke, dust, pollen, and germs. You might also add daily medications to improve symptom control.

Track Your COPD Diet and Treatments

You can improve life with COPD by taking part in the management of your condition. One way to help your doctor is to monitor your COPD symptoms, diet, and exercise daily.

Keeping a daily written log may help you recognize a COPD exacerbation when it begins. With a log, you’re more likely to notice when COPD symptoms suddenly get worse. This may allow you to seek medical treatment early, when it’s most effective, and might keep you from having to go to the hospital.

It is also important to follow a healthy, balanced diet to prevent being overweight, which can make shortness of breath worse, or underweight, which is linked to a poorer outcome. Your doctor or a nutritionist can suggest healthy food choices for you.

Use your log to track these things each day:

- Symptoms, such as cough, shortness of breath, increased mucus, and fatigue

- Medications and dosages

- Diet

- Exercise and other physical activity

When Should I Call 911?

Get medical help right away if any of these things happen:

- You have severe shortness of breath.

- You can't walk or talk.

- Your heart beats very fast or has an uneven beat.

- Your lips or fingernails turn blue.

- You breathe fast and hard, even when taking medicines.

Takeaways

COPD makes it hard for you to breathe and tends to get worse over time. But there are lots of things you can do to slow it down and feel better. Work with your doctor to come up with a management plan that gives you the best quality of life possible.

COPD FAQs

What is the life expectancy for a person with COPD?

The exact amount of time you can live with COPD depends on your age, overall health, and symptoms. If you have mild, well-managed COPD, you might live for 10 or 20 years after your diagnosis. Your life expectancy is shorter if you have severe COPD, which takes an estimated 8-9 years off an average person's life. Life expectancy is shorter at any stage if you smoke

How does a person with COPD feel?

When you have COPD, it can feel like breathing takes more effort and you are gasping for air, especially when you are active. Your chest might feel tight and heavy. You might feel tired all the time.

Can I live a normal life with COPD?

Many people can live an active life with COPD. The key is follow your doctor's recommendations for managing your condition, with medications, a healthy lifestyle, and other supports, such as pulmonary rehabilitation. Joining a COPD patient support group could help as well.